Richard Hongisto was a cat with more than nine lives. He was a United States Marine, a police officer, a television reporter, the elected Sheriff of San Francisco, the Cleveland Chief of Police, the New York Commissioner of Corrections, an elected member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the elected San Francisco County Assessor, the San Francisco Chief of Police and the owner of a private security company.

That’s actually ten career lives and they don’t even include his private real estate holdings, his Ph.D. candidacy in criminology at the University of California Berkeley, his several marriages, or his brief ownership of the amazingly-named “Vote Hongisto Market.”

Dick Hongisto was far more colorful and controversial than a summary of the various notable dates in his public career and the amazing array of public offices he held. He thoroughly enjoyed the limelight and seemed to create his own star-power with very little effort.

In 1972, his second year as Sheriff, Richard Hongisto held a press conference to famously tell San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto to “kiss my ass” and to inform the national media that he "wouldn’t support Alioto for dogcatcher in the smallest county in California.”

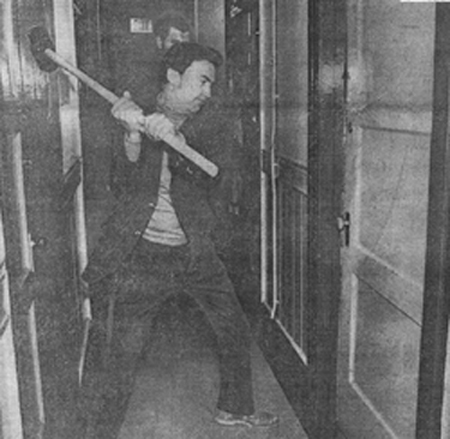

Sheriff Richard Hongisto was held in contempt of court and sentenced to jail for refusing to evict a hotel full of elderly Filipino residents at the International Hotel in North Beach. In his typical contrary style, Hongisto later carried out the International Hotel eviction and was photographed swinging a sledgehammer through a tenant’s door. Dick was the exact opposite of uncomplicated his entire life.

In the 1960’s Dick Hongisto served as a San Francisco police officer, became a founding member of an historic African American officer’s group called Officers for Justice, and then positioned himself to become known as a community liaison officer for San Francisco’s growing gay and lesbian communities.

Then, in move typical of the way he lived his life, he abruptly resigned from the San Francisco Police Department and worked briefly as a spot reporter on the KQED televised news program "NewsRoom". Out of nowhere in 1971 Dick Hongisto publicly declared his candidacy for the office of San Francisco Sheriff, joining two other candidates in challenging the sixteen year entrenched incumbent, Matthew C. Carberry.

The Election of 1971: New Voters and a Wave of Reform

The race for the office of Sheriff in the City’s November 1971 General Election was a free for all with incumbent Sheriff Matt Carberry seen as out of touch and vunerable. Carberry was a wounded candidate, both professionally and personally and there was a definite feeling political blood was in the water. A Blue Ribbon Commission on Crime had roundly criticized Carberry's administration and he had a well-known public drinking problem, taking several leaves of absence to address that problem and to avoid being suspended by Mayor Joseph Alioto.

On June 17, 1971 San Francisco Police inspector William (“Bill”) Bigarani became the first to declare his candidacy for the office of Sheriff.

Supervisor Matt Carberry was appointed by Mayor George Christopher to fill Sheriff Daniel Gallagher's term of office after he unexpectedly died on May 6, 1956. Carberry went on to win three more four-year terms, serving as San Francisco's Sheriff for almost 16 years.

Next to declare his candidacy for sheriff was Matthew M. O’Connor, 46, the chief of the State Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement, described by the SF Chronicle as "Northern California's top narcotics official since 1958".

On July 20, 1971 O’Connor came out swinging, stating “the San Francisco jails under the present administration are nothing more than large, noisy flop houses for criminal elements.” But O’Connor had actual campaign talking points, specifically a plan to give mental assessments to all prisoners when they entered the jail and to recruit more minority staff to improve communication with minority inmates.

Richard Duane Hongisto announced his candidacy on August 16, 1971. Born in Bovey, Minnesota on December 16, 1936, Hongisto's Finnish immigrant parents moved the family to San Francisco in 1942 where he went to George Washington High School and City College. He joined the the San Francisco Police Department and at the same time completed a bachelor's degree at San Francisco State University.

After ten years on the police force Hongisto was working on his graduate degree in criminology at UC Berkeley and was eager to find a public platform for his innovative criminal justice ideas. He ran as an intellectual pipe-smoking crime fighter, but also as a champion of gay rights.

Hongisto's first remark at his announcement press conference was, “I hope that this race doesn’t degenerate into a lot of mudslinging.”

What followed almost immediately after that pronouncement was a pure dose of unedited Dick Hongisto:

• He described incumbent Sheriff Matt Carberry as “the greatest tutor of crime on the West Coast….”

• “[Carberry] through sheer neglect and ignorance… has an unblemished record of nothingness….”

• Hongisto promised “to give $750 a month off the top of my salary to neighborhood groups to deal directly with their problems.”

• He linked the current trends in law enforcement with the morass of the current war in Vietnam, describing Carberry and O’Connor as “hawks”.

On August 26th incumbent Matt Carberry, now 60 years old, finally officially announced he was running for re-election. There was a sense among local news reporters that San Francisco was rapidly changing and Carberry would have a difficult fight ahead to keep his job.

Matt O’Connor was endorsed by the SF Deputy Sheriff’s Association and the Black Deputies of the Sheriff’s Department group. Richard Hongisto won the support of the Officers for Justice-- the African American SF police officers association. Hongisto also had the endorsement of SF Assemblyman Willie Brown, who the Chronicle described as campaigning and raising money “vigorously” for Hongisto.

Carberry got the San Francisco Chronicle’s endorsement on October 29th.

On September 15th candidate Matt O’Connor filed a $40,000 damage suit against Bigarani in Superior Court for “invasion of privacy”. O’Connor charged that a Bigarani campaign staffer, posing as a credit investigator, went to the location of one of O’Connor’s three residences and questioned neighbors. O’Connor lived in San Mateo County for a time but the SF Registrar of Voters had previously ruled that O'Connor met San Francisco’s five year residency rule for political candidates and the lawsuit went nowhere.

The November 3rd election day voting went overwhelmingly for Richard Hongisto who managed to carve out a victory with less than 40% of the vote in the days before run-offs or the requirement of a majority vote:

• Richard Hongisto 81,403

• Matt Carberry 59,848

• Matthew O’Connor 49, 802

• William Bigarani 33,015

Carberry accurately summed up the voting by saying he and O’Connor and Bigarani split the moderate and conservative votes allowing the more liberal voters to hand the election to Hongisto. But there is little question that the serious problems and incidents at San Francisco’s jail in San Bruno over the previous four years proved to be a difference-maker to the voters. Gracious in defeat Matt Carberry declared that “Mr. Hongisto has my good will and good wishes.”

Richard Hongisto announced he spent $16,544.85 on his successful campaign for sheriff, with exactly 90 cents left in his reelection fund at the end. William Bigarani spent $20,000.

Reporter Michael Harris of the Chronicle expertly deciphered the inside story of the 1971 race for Sheriff. Harris noted that Assemblyman Brown had his eye on a run for Mayor in 1975 and expertly helped put together four very new and powerful voting blocks for Hongisto: the young, minority men and women, liberal adults, and the City’s 30,000 gay voters. Brown told Harris that no one planned Hongisto’s campaign as a test run for his own race for mayor in 1975, “But his [Hongisto’s] campaign,” stated Brown, “is the one we are going to use as a measurement-- as a good reference point.”

Speaker Brown would indeed become Mayor of San Francisco, but that wouldn’t happen until the General Election of November 1996.

Richard Hongisto ran for a second term as Sheriff in the November 1975 election. He was opposed by five other candidates, including William Bigarani again. Hongisto won overwhelmingly receiving 96,009 votes; the other five candidates combined to get 97,489 votes.

Early on it was clear that the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department was in for a very rocky ride. In just his fourth month as Sheriff, Dick brought the press into the county jail to watch him eat dinner with the prisoners and hear him say, “I’m a liberal, maybe even a radical.”

Dick hired San Francisco's first African American Undersheriff, Reuben Greenberg, and the City's first openly gay deputy sheriff, Rudy Cox. He worked tirelessly with the gay and lesbian communities to recruit and hire gay and lesbian deputies, something unheard of anywhere in national law enforcement. When inmates in the forty year old and aging San Bruno jail protested conditions by setting fires to their mattresses, deputized staff declared it a riot. But Sheriff Hongisto termed it “a peaceful fire demonstration.”

Hongisto had his personal Sheriff's badge modified, removing the City seal and replacing it with the international peace symbol.

While San Francisco’s prior Sheriffs had few programs for inmate work projects, inmate farming or inmate education programs, Sheriff Hongisto made prisoner rehabilitation the hallmark of his administration. Hongisto invited San Francisco's Community College to teach classes inside the county jails; he created a relationship with the fledgling, and very liberal, New College of California to bring in students into the jails to serve as social workers; he allowed the Bar Association to sponsor a full time prisoner assistance lawyer, and brought in work study law students to address to prisoner problems; he created an Office of Ombudsman to administer an effective inmate grievance system.

In 1971 the San Francisco Bay Guardian called Hongisto "the notable exception" in the search for a political ray of light in difficult times.

Hongisto was decades ahead of social-cultural reforms, supporting the personal use and possession of marijuana by endorsing Proposition 19, the 1972 California voter initiative to legalize marijuana. The initiative lost by a margin of 66.5% to 33.5%. Throughout his public career Hongisto never waivered in his opposition to draconian drug laws and penalities.

Dick Hongisto was the first San Francisco elected official to ride in the annual San Francisco Gay Parade. He also was an early and big supporter of Castro District activist Harvey Milk’s campaign for the Board of Supervisors, and was famously photographed riding a motorcycle beside Harvey, on his way to City Hall on election night November 1977.

As Sheriff, Dick was determined to improve conditions in San Francisco’s county jails. He opened the jails to groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Friends Outside. He created his own non-profit organization, called Friends of Deputies and Inmates, so he could accept gifts and donations to the jails without having to first get approval by going through the Board of Supervisors.

Hongisto Engineers the Merger of the City’s Dual Jail Systems

Within the unique configuration of a combined City and County government the responsibilities of the county Sheriff’s Department and city Police Department have sometimes been convoluted and at odds. In the case of San Francisco’s jails, the Police Department had traditionally managed the booking and intake of newly arrested persons in a series of separate “booking” jails for over a hundred years; at various police stations, in both versions of the Kearney Street Hall of Justice and now at the Bryant Street Hall.

The Sheriff’s Department was responsible for managing the City’s “housing” jails.

In 1973 the SFPD’s booking facility was called “City Prison”, located on the 6th floor of the Bryant Street Hall of Justice. The Sheriff’s Department’s two housing jails were County Jail No. 1 on the 7th floor of the Hall of Justice and County Jail No. 2 San Bruno.

In November of 1973 the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved consolidating all City jails under the Sheriff’s Department. Not surprisingly the move was supported and opposed by various political entities.

In the 1950s and 1960s Sheriff Matt Carberry had made several attempts to bring City Prison under Sheriff’s management, but two different mayors turned him down. Carberry relied on the logic of consolidation and was not the kind of coalition-builder who could conceive and implement a political agenda. In reality Carberry was lucky not to have his budget cut each year. Since 1955 there had been 10 specific municipal reports recommending that the two jail systems be combined, but in April of 1973 the mayor’s Criminal Justice Council endorsed the merging of City Prison and the county jails under the Sheriff’s Department.

The Criminal Justice Council forwarded that recommendation to the Board of Supervisors and the wheels of city government began grinding. But in the background throughout the entire jail merger project was Sheriff Richard Hongisto’s deft political maneuvering and sleight of hand.

Hongisto wanted the jails consolidated but realized that the proposal could not come directly from him. The San Francisco Police Officers Association, the police “union”, was adamantly opposed to giving up City Prison to the Sheriff’s Department and they frequently had the political clout to get what they wanted. Hongisto knew that if the jail consolidation issue became a one-on-one law enforcement grudge match a number of elected city officials would back the POA.

During and after his election, Richard Hongisto developed some key political allies and he had several on the mayor’s Criminal Justice Council. On April 3, 1974 the Council went public with their jail merger plan, and Hongisto was right there to follow up their recommendation with potent political bullet points:

• He noted it would free up the 40 police officers then assigned to City Prison to fight crime on San Francisco’s streets;

• Since deputy sheriffs received lower pay and fringe benefits than police officers, Hongisto stated that “consolidation would save the City $200,000 a year”;

• Jail medical and administrative procedures would be streamlined and cost less.

Curiously at the same time, the Council authorized Sheriff Hongisto to apply for $1.1 million from the California Council on Criminal Justice for jail improvements. He stated that he had 20 major projects on which to spend that money if he got it. Although Mayor Alioto and Hongisto continually locked political horns, it was noted by Chronicle reporter Kevin Leary that just prior to the Council issuing its various recommendations, Alioto had appointed a new member to the Council and then re-appointed four incumbents.

On November 12, 1973 the Board of Supervisors approved in principal the consolidation of the City’s two jail systems and formed a committee to draw up detailed merger plans. The action was supported by Police Department management and predictably opposed by the Police Officers Association. But it wasn’t until November 18, 1974 that the Board finally voted to get consolidation done by unanimously passing an ordinance giving the sheriff jurisdiction over City Prison and a resolution urging him to submit a formal budget request for staff and equipment.

Then Richard Hongisto played old school political hardball by twice suggesting the jail merger, which he wanted and helped to orchestrate, might not happen after all.

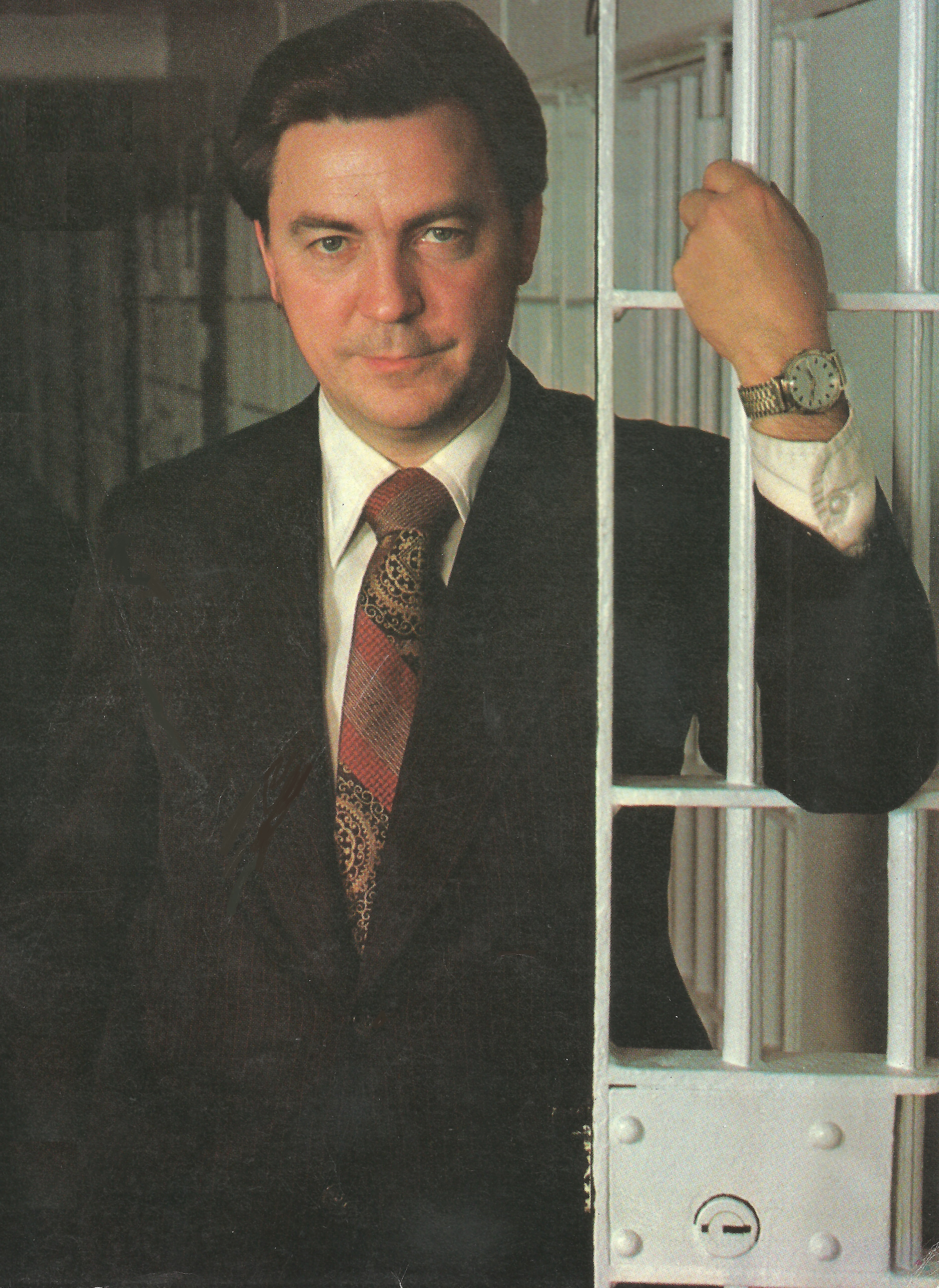

Sheriff Hongisto was interviewed by "San Francisco" magazine in July 1977 and asked about serving five days in the San Mateo County Jail for contempt of court stemming from his refusal to conduct evictions at the International Hotel. "I basically haven't taken any vacations, in the ususal sense of the word", Hongisto stated, "so it was kind of nice just to do something different for five days." Photo by Ron Shuman.

Then on February 6, 1975 San Francisco City departments submitted their upcoming fiscal year budgets. Hongisto asked for an additional 289 deputy sheriffs, increasing his budget from $6.6 million to $12.5 million a year. The Mayor’s office summarily cut Hongisto’s budget request down to virtually nothing, dismissively giving Hongisto only 10 new deputy positions to run City Prison. Displaying outrage, Hongisto immediately went to the Board of Supervisors and informed them, “They [the mayor’s office] cut everything but the barest possible staff. Unless something changes I’m abandoning consolidation in the next fiscal year.”

With the Mayor, the entire Board, the Police Department and media all in favor of and anticipating the jail merger Richard Hongisto realized he had the upper hand in a high stakes political game.

“I don’t want to perpetuate bad government”, Hongisto told the Board. “The staffing as proposed by the mayor’s office would not only not improve City Prison it would hurt my department. I don’t want to go ahead with consolidation at the expense of screwing up the Sheriff’s Department.”

The Bar Association of San Francisco immediately slammed city officials for the merger holdup and demanded that the budget issues be resolved. And after months of wrangling and finger-pointing, the Mayor's office grudgingly agumented the Sheriff's budget to Richard Hongisto's satisfaction.

At a September 5, 1975 press conference a glowing Sheriff Richard Hongisto announced his department would start taking over the operation of City Prison in October 1975, with 27 new deputy positions and 4 new sergeant positions.

The Unending Struggle to Improve the County Jails

Hongisto spent virtually his entire time as Sheriff trying to improve and maintain the county jails. He continually had to fight for budget allocations from the City, pressed for grant money and direct donations, and sought State and Federal resources to improve prisoner programs and education. The San Bruno jail was particularly challenging, not only to establish an array of improved inmate services but needing to play catch up on decades of deferred physical plant maintenance. Hongisto installed showers on each of San Bruno's six jail tiers and converted a hallway of underused storage rooms in the jail's administraive wing to be used for a variety of inmate classrooms.

Hongisto talked the famous rock promoter Bill Graham into sponsoring a benefit at Winterland Auditorium to raise money for the county jail inmate welfare fund. That concert featured David Crosby, Graham Nash, Neil Young, Elvin Bishop, and the group Stoneground. The concert was on March 26, 1972 with tickets selling for $3.50 in advance, $4.00 at the door.

To dramatize the lack of funding for the jails, for several days Hongisto came to work at his City Hall office dressed in tattered and torn inmate clothing. “I just want to get the job done,” the 37-year-old sheriff told newsmen. He was outfitted in ripped pants, socks with holes, truncated shoes and a threadbare shirt – standard jailhouse issue to all inmates at the time. “The shoes have the toes cut off so they’ll fit feet of any size.” (Eugene Register-Guard. 2-10-1973)

It was at this time that the Sheriff blasted Mayor Joe Alioto for giving the jails only $25,000 of federal revenue sharing funds out of the $800,000 that Hongisto had requested.

Hongisto quickly garnered a national reputation as a criminal justice crusader and champion of minority rights. He handily won his second election against four opponents. Hongisto’s abbreviated second term was filled with contentiousness and legal controversy. Although he served only two years of his second four-year term, it seemed like Dick Hongisto was constantly in the media and making national headlines every other week.

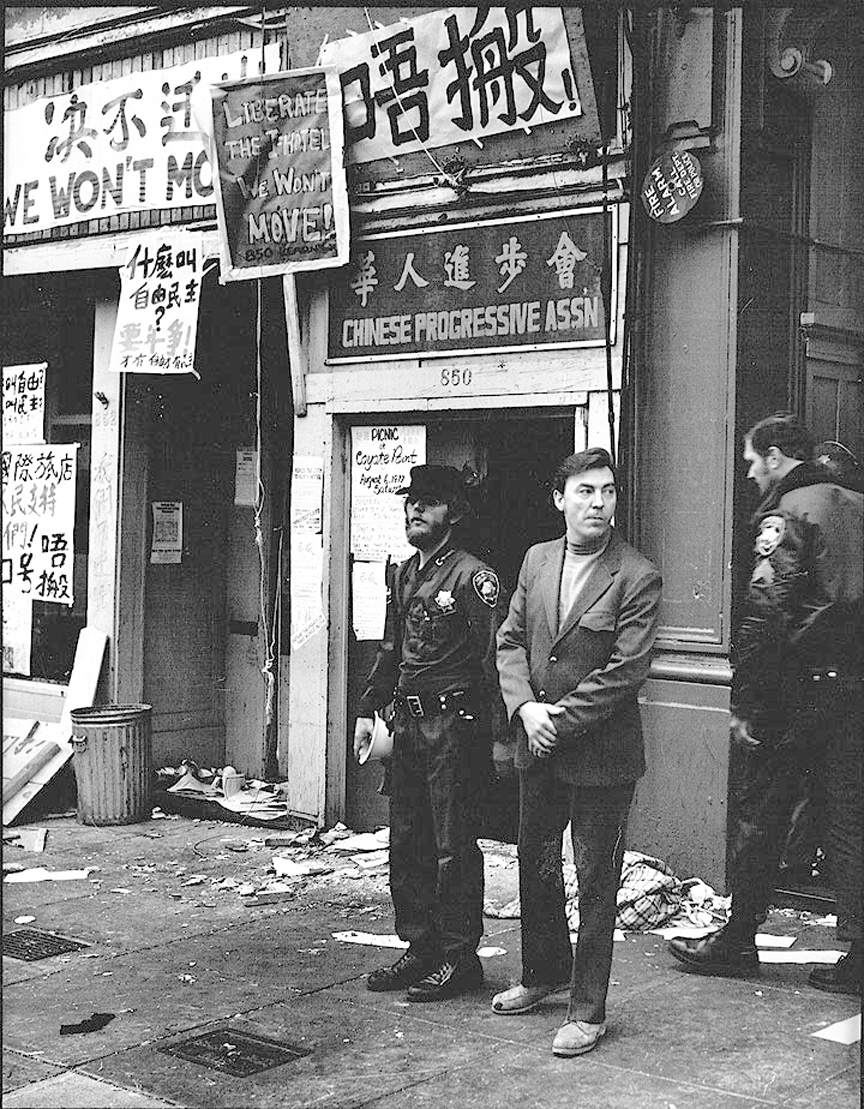

The International Hotel at the corner of Kearny and Jackson Streets was a low-cost residential hotel built in 1907. The first eviction notices were served by the courts in 1967. It was demolished in 1981.

Three specific episodes were especially controversial: his alleged association with the New World Liberation Front, his contempt of court conviction, and his eviction of tenants at the International Hotel.

The mid-1970’s were radical times in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Symbionese Liberation Army and the Weather Underground laid the groundwork for the creation of another lesser known radical group based in San Francisco: The New World Liberation Front.

The NWLF claimed responsibility for over 50 bombings between 1974 and 1977, including placing bombs at the homes of Dianne Feinstein and John Barbagelata, both members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Jacques Rogier was the spokesman for the NWLF and he funneled one or more “communiqués” to the media through Sheriff Richard Hongisto.

This infuriated Feinstein and Barbagelata who accused Hongisto of collaboration with the NWLF terrorists. There was never any evidence that Hongisto was involved on any level with the NWLF other than as a conduit for media information, but bitter feelings lingered over the issue for years.

By far the biggest incident that clouded Hongisto’s second term was the International Hotel eviction, which played itself out in two stages.

The I-Hotel was an old, decrepit building on at the corner of Kearny and Jackson Streets on the edge of Chinatown and the Financial District. It was home to many poor elderly Filipino men and women. A foreign corporation purchased the building with the intention of replacing it with a modern high-rise hotel and office building. The potential eviction of some 196 residents became a flash point for local activists and organizations, including Jim Jones of the People's Temple who turned out hundreds of protestors to stop the eviction.

Sheriff Richard Hongisto and Undersheriff Jim Denman in front of the International Hotel, 1977. (Calvin Roberts, Granmas)

Hongisto told People Magazine, "If going to jail is all I have to pay for following my conscience then it is a very small price."

Hongisto’s refusal to enforce the eviction made him a hero with the City’s activists, but not with Superior Court Judge Ira Brown who ordered him charged with contempt of court in December 1976.

In January, Hongisto was the defendant in a week-long trial that was held in City Hall before Judge John Benson. As the trial ended, but before the verdict was known, Dick’s attorney Richard Mazer was questioned by the media outside the courtroom about the possibility of the Sheriff going to jail. In one of the greatest lawyer statements of all-time, Mazer said, “He’s not going to jail. If he gets any jail time, I will do it for him.”

Sheriff Hongisto was found guilty of contempt of court, fined $500.00 and sentenced to five days in the county jail, to be served in the San Mateo County Jail to avoid receiving any favoritism in his own jail facility. After a brief attempt to appeal the decision, Hongisto did his jail term the first week of May 1977.

Dick was a celebrity prisoner, keeping a journal, giving an array of media interviews and being greeted by a crowd of flower carrying well-wishers upon his release.

The good will he enjoyed from San Francisco progressives was short lived as he faced the prospect of again being ordered to enforce the evictions at the International Hotel.

On August 3, 1977, hundreds of San Francisco Sheriff deputies and police officers surrounded the International Hotel and the thousands of shouting protestors who had gathered on the streets. Sheriff Hongisto and his deputies entered the Hotel and went room to room in order to insure that everyone had vacated the building. Since many of the rooms were locked, a number of forced entries were required.

Sheriff Hongisto invited a press photographer to accompany him during the eviction. At one point, Hongisto took a sledgehammer from a deputy sheriff, swung it high and smashed through a locked door. That press photo became an icon for the rest of Hongisto’s career.

Whether the International Hotel eviction incident would have been the final straw for Sheriff Hongisto will never be known, but just a few months later he flew to Cleveland, Ohio to meet with Mayor Dennis Kucinich about becoming Cleveland’s new Chief of Police.

Two years into his second term of office, Richard Hongisto resigned as Sheriff on December 11, 1977, having moved to the city of Cleveland a few days before.

Some months after that, future-Sheriff Mike Hennessey went out for drinks with Dick and asked him why he made such a sudden and dramatic move. Hongisto explained that he felt politically “stuck” as Sheriff in San Francisco. He had surveyed the political landscape and saw Mayor George Moscone certainly running for and winning a second term; and that Phil Burton and his brother John, and Willie Brown and Alan Cranston weren’t going to be stepping down and providing any possible political openings for him to pursue in the near future.

So his potential for advancement was more likely within the law enforcement field and he needed a broader resume than that of San Francisco Sheriff.

And, while his predictions about the potential vacancies in local and state political offices would be off the mark, Richard Hongisto's quest for a broader and more varied public resume was only just beginning.