There are hundreds of ways to escape from a jail or prison and some of them, unfortunately, include the active participation of staff.

On Sunday April 27, 1980 there was a mass escape of thirteen prisoners from County Jail #2, the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department’s high security jail on the 7th floor of the Hall of Justice. I had just been sworn in for my first term as Sheriff on January 8, 1980, so this was a blockbuster incident. Housed in County Jail 2 at the time of the escape were members of the Hells Angels biker gang, who were not part of the escape scheme and who passed up the opportunity to join the escapees. The Angels believed that they would ultimately beat the federal cases against them and didn't want to risk any additional criminal charges. Some of the Angels eventually did beat their cases, but a dozen or so others got a hung jury in their trial and the US Attorney decided to prosecute them a second time.

Sergey Walton was the former president of the Oakland, CA chapter of the Hells Angels motorcycle club, founded in 1957.

Walton was a top lieutenant under Sonny Barger, co-founder and president of the Oakland Chapter of the Hells Angels, and in the past had been the subject of numerous murder investigations. Although no longer the Oakland president, he was still considered one of the most influential of California’s Hells Angels.

By 1981 the remaining Angels had been in the San Francisco County Jail for over two years and may have been getting a little antsy. Then, on March 27, 1981 inmate Sergey Walton “turned up missing” at County Jail #2. Federal marshals had come to the jail to pick him up for transport to another facility, but he wasn’t in his cell and there were no clues about how he could have gotten out of the cell, let alone escape from the jail.

After a few days of fruitless searching and interviewing both prisoners and staff, suspicion fell on two deputy sheriffs: a 15-year veteran deputy sheriff, Lou Ivankovich, and Sgt. Joan Nimau, the first woman supervisor to work in the Department’s maximum security men’s facility.

Joan Nimau brought the suspicion upon herself. On one occasion, after the criminal charges were dismissed for many of the Angels, she brought them a cake adorned with the saying, “Goodbye RICO.” And to make things worse, she had written Walton a letter of recommendation for bail, saying, “I will always consider my association with Sergey Walton and the other Hells Angels as one of the most positive experiences I have had in my career. I find it difficult to try to write all the respect and admiration that I feel for Sergey. In short, I consider him a friend.”

The letter was written on Department letterhead, under my name. This caused my salty Undersheriff, Bill Davis, to inappropriately remind me, “Mike, how many times do I have to tell you? Never let an ugly broad work in a men’s jail.”

It seemed unlikely that Joan had been involved in the actual escape, but coincidences always lead to inquiries. Joan had resigned from the Department prior to the escape and her last day of work was just three days before Walton disappeared. Her husband, a San Francisco police officer, resigned a week later. They immediately moved out of state. Ultimately, no charges were ever brought against Joan Nimau.

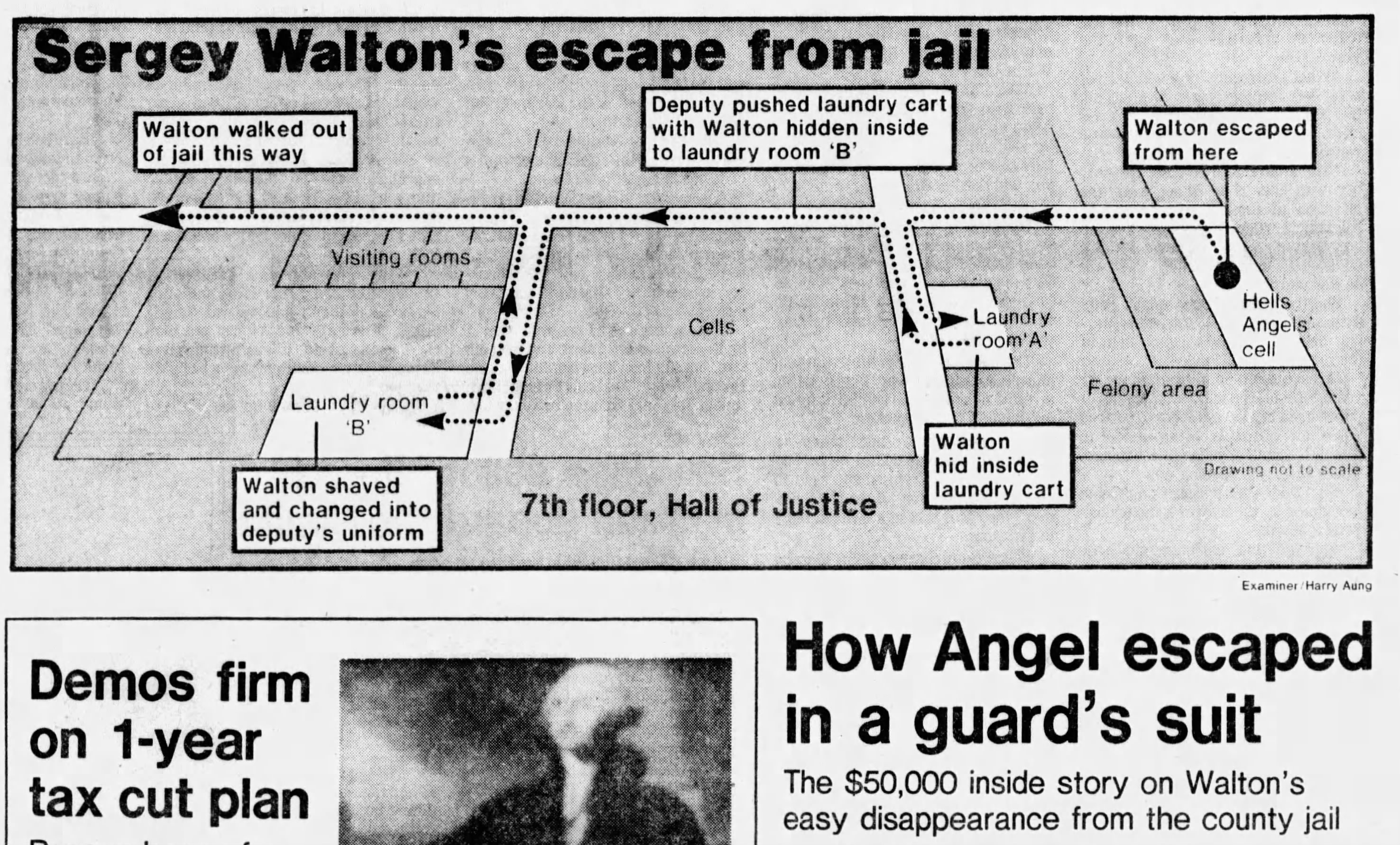

The San Francisco Examiner's front page from May 29,1981 with a diagram of County Jail #2. Based on interviews with "jail inmates and law enforcement sources", the article suggested Walton's escape route and speculated that he wore a deputy's jumpsuit as part of his escape plan. None of which proved to be true.

A couple of nights after the escape, Lou “slipped on some water on the locker room floor” and went off work, claiming a job-related disability. He became unavailable for interview and soon engaged the services of a lawyer. But, in truth, we had very little on him other than opportunity and the elimination of other possibilities.

Over the course of the next several months we monitored phone activity at the Ivankovich house and other places where we thought we could glean information either about the escape or the whereabouts of Sergey Walton. There were numerous phone calls between Lou’s house and Sergey Walton’s wife. Undercover officers followed Lou as he drove around in his newly acquired Pontiac Firebird. Eventually I felt we had enough to terminate Lou, even if the US Attorney wasn’t prepared to prosecute him. Unfortunately, under the Civil Service rules at the time, you could not terminate or suspend an employee while they were out on a disability leave.

We worked with Lou’s doctor to convince him that we had a “light duty” job filing papers that Lou could perform without exacerbating his injury from the fall in the locker room. The doctor cleared Lou for light duty work and during his first hour back at work we served him with termination papers and he was immediately suspended from duty.

Lou’s termination case was put on hold and when he was later charged with a federal crime, the matter was closed without the necessity of a hearing.

Not long after Lou was served with papers, the phones started chattering again and, thanks to the phone tap along with some promising tips, a task force of law enforcement agencies converged on a small house hidden away in the Santa Cruz mountains near Felton. On May 28th 1981, more than a month after the escape, members of the task force approached and surrounded the house. Sergey Walton ran out the back door across the property and had one leg over the backyard fence when he was confronted by officers with drawn weapons. He dropped to the ground and gave up without a struggle.

The federal authorities were intent on discovering how Walton had escaped. At one point a federal grand jury was investigating a rumor that a San Francisco sheriff’s deputy had received a bribe of $50,000 to facilitate the escape. That allegation was never proven.

It took over a year, but eventually the US Attorney brought criminal charges against Lou Ivankovich. On February 18, 1983, Lou’s attorney unexpectedly stood up in court and told the judge that his client wanted to change his plea to “guilty.” In open court, Lou admitted that he pushed the jail laundry cart to the elevator with Walton in it. His attorney later told me that he was taken totally by surprise by Lou’s admission. Lou was sentenced to three years in federal prison.

So, why did he do it? Lou never spoke about it that I know of, but Walton did.

After Sergey Walton was ultimately convicted in his Federal organized crime case and was given a prison sentence, I sought him out in the jail. I asked him if he would tell me what really happened. His response was pretty surprising.

“Well, it wasn’t the first time Lou got me out, you know,” is how he started the story. Off duty, Deputy Lou Ivankovich was a biker – and even on duty he looked the part: a big husky guy with a gut and a beard. So the seduction started with stories about bikes, beer parties and tales of legendary “runs.”

After establishing a many months long camaraderie over bikes, Walton told me, he joked around with Lou and said, “I’ll bet you could get me out of here for a beer and get me back in without anyone even knowing about it.” According to Walton, Lou agreed that he probably could since he was the senior guy on the watch and other deputies left him pretty much alone.

Then, much to Walton’s surprise, one night Lou unlocked his cell door and said, “Come on. Get in the cart.” A laundry cart almost full of sheets and blankets was in front of the cell. Walton said that he got in, was covered with laundry and the next thing he knew he was in an elevator going downstairs. Lou rolled Walton out to a loading dock, where they drank some beer which had been stashed in the basement, and then took the elevator back up to the jail. Walton said he could have escaped then, but he was completely surprised and didn’t have anything set up.

A week later, Walton challenged Lou to set up another beer run. But this time he arranged to have a car waiting downstairs. At Walton’s sentencing in Federal court in February 1983, his attorney made this startling statement: “It was Mr. Walton’s intent to return to custody. He would have returned to the jail as he had a week before after a 24-hour absence if US Marshalls hadn’t come to pick him up to transfer him to another prison and found him missing.”

Walton was eventually sentenced to 10 years in Federal prison, to be served after completion of an eight-year sentence for his prior conviction for possession of the machine gun. He later became an informant for Federal government prosecutors and entered the witness protection program and was secretly relocated. Sergey Walton died on October 19, 2006 at 62 years of age; he had been residing in Sacramento.

On the day of Walton’s sentencing for the escape, sitting in the public section of the Federal courtroom with full Hells Angel’s colors flying, was the ultimate leader of the Angels, Sonny Barger. It’s unknown whether he was there to lend support to his brother Angel Sergey Walton or to stare down the man who violated the biker code of not ratting out. But whichever the case, Sonny Barger couldn’t have been pleased about the ultimate outcome of the Hells Angels infamous San Francisco County Jail beer runs. Barger died on June 29, 2022 at the age of 83 of liver cancer.

Next: Dialing the Impossible Down to Difficult: Building Jails in San Francisco