California Becomes the 31st State and Capital Punishment is Delegated to the Counties

One of the most difficult of duties for the early California sheriffs was the execution of prisoners who had been sentenced to death. From 1850 to 1890 the sheriff in each county conducted all lawful executions in California. During these forty years, there were over two hundred thirty executions in the various California counties, virtually all by hanging.

Executions varied greatly from county to county. A typical hanging involved only one condemned prisoner, but there were several occasions when two or three prisoners were hung, side-by-side. In 1861, Tuolumne County authorities conducted a group execution of four Chinese men, and in 1863 the military hung five Native Americans simultaneously.

Most executions went relatively smoothly with the condemned man allowed time for a short statement. Sometimes the man about to die sang a song and one man even invited a harpist onto the gallows so he could “dance his way out of the world.” (Jose Sebade, Tuolumne County, 1855). It was not uncommon for the condemned man to be drunk when led to the gallows or so ill or distraught that he had to be carried.

On numerous occasions the execution was botched, with the murderer’s head being snapped off from the fall (Marshall Martin, Contra Costa County, 1874) or the noose coming untied during the drop, necessitating a “do over.” Once in El Dorado County both nooses of two men being hanged together came untied during the drop and the proceedings had to be staged a second time (James Logan, William Lipsey, 1854).

During the time California's counties were responsible for capital punishment, San Francisco Sheriffs conducted eighteen executions. The first two were held in public, with up to ten thousand spectators attending, creating a circus-like atmosphere. To avoid such spectacles, in 1856 Sheriff David Scannell moved the executions to a gallows erected for the occasion in the enclosed yard of the county jail on Broadway. Several hundred spectators were invited to attend, mostly public officials, the press and civic leaders. Moving the executions to the jail yard did not, however, eliminate gawkers, as people eager to catch a glimpse congregated behind the jail on Telegraph Hill and on nearby rooftops. As many as a thousand of the curious gathered in the street in front of the jail for each execution, even though they could see nothing except perhaps the removal of the body after the execution.

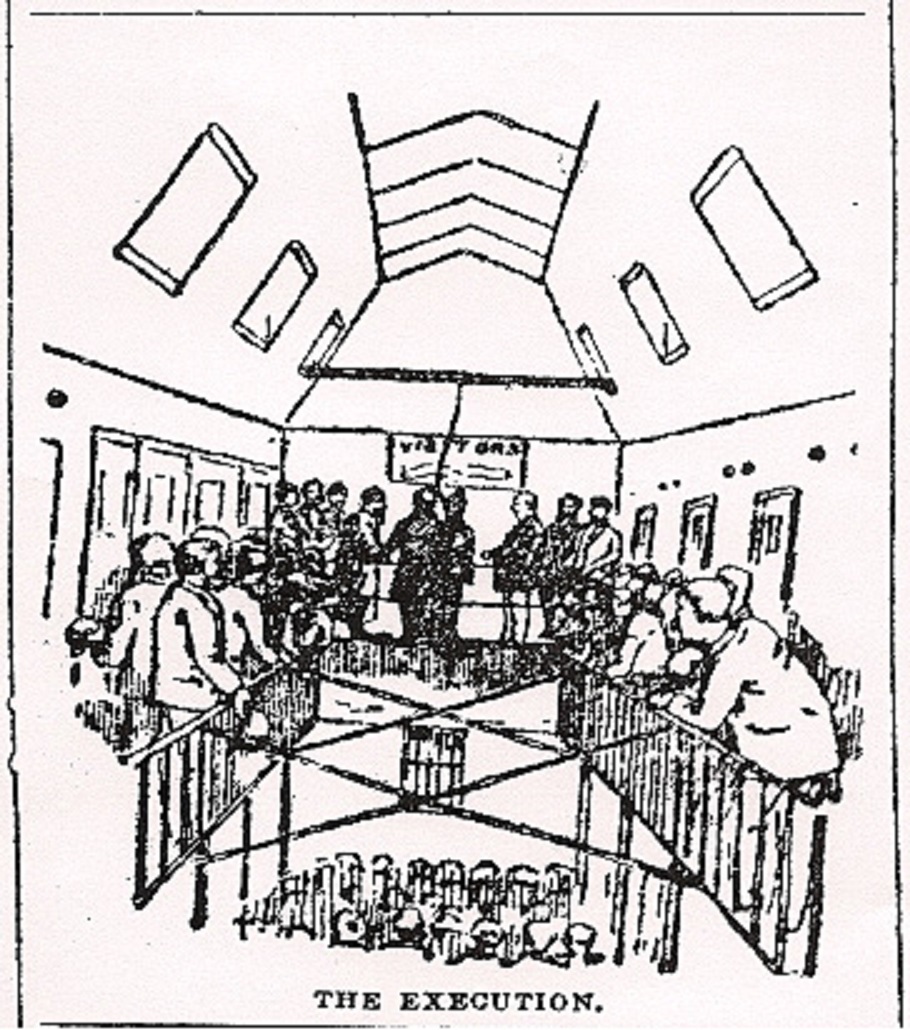

In 1866, Sheriff Henry Davis changed the protocol yet again by creating a makeshift gallows inside the county jail, using a cross beam attached to the rooftop windows and a hinged platform added to the second floor walkway. Invited spectators stood on the walkway in front of the second floor cells and in the center aisle on the first floor. The body of the executed man dropped right in front of the first floor audience. San Francisco executions remained inside the jail in this fashion until state law removed executions from the counties to the state prison in 1891.

The Clamor for Execution Invitations

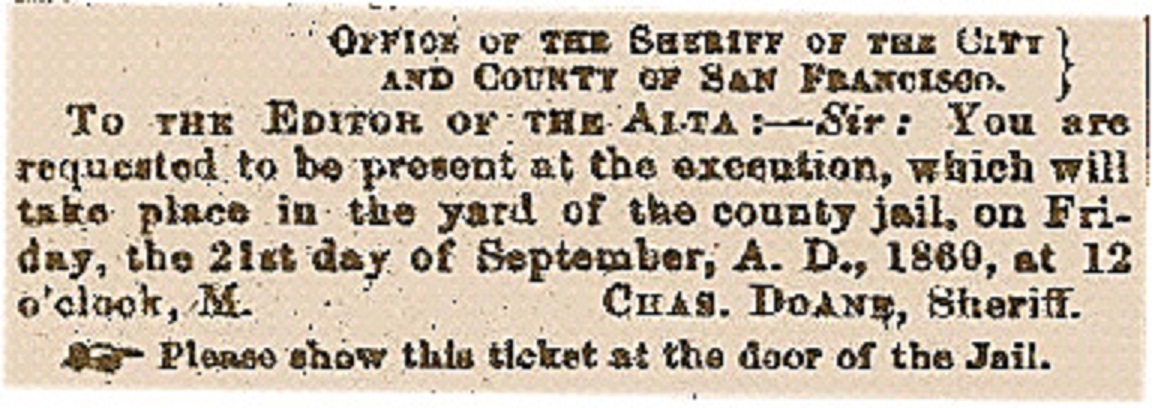

An invitation to an execution was a hot ticket. The Sheriff typically invited members of the press, public officials and personal friends. On many occasions, a newspaper editor would publish the Sheriff’s invitation in the newspaper. As can be seen by the newspaper stories that follow, the clamor for execution tickets only grew over the years.

Sheriff Charles Doane had this invitation to an 1860 execution at the Broadway Street Jail published in The Daily Alta California newspaper. The announcement doubled as a ticket to view the execution.

Rush For Admission Tickets

Up to 2 o’clock in the afternoon the Sheriff’s office was besieged with applicants for invitations to the execution. So great was the demand that Sheriff Connolly was obliged to seek shelter in the County Jail, while Undersheriff Cummings had to hide himself in the old City Hall to escape the mob so morbidly eager to see a human being meet a sudden and horrible death. In all there were some 2,000 applications, but only 350 cards were issued. Of this number 52 were sent to the Sheriffs of the different counties, of whom some eight or ten will probably be present. The other cards were distributed among the city officials and newspaper offices. The jail will not comfortably hold more than 250 spectators, and it is not likely that more than this number will attend.

-- The San Francisco Examiner January 23, 1884

This article is in relation to the execution of George Wheeler. At his execution, Wheeler was given a small glass of whiskey moments before the hanging, “and then, turning to the Sheriff he thanked him for the favors he had received at his hand, and said he would like to express his thanks from the gallows. The Sheriff replied: 'If you wish to do me a favor George, say as little as possible and die like a man. Do not give us any trouble.' 'I promise you that,' was the reply, shaking him by the hand." (SF Examiner, Jan. 24,1884)

At the execution of Chin Mook Saw in 1877:

There gathered on Broadway, in front of the jail, nearly a thousand men and boys, and, we are sorry to say, women and young girls, drawn thither by this morbid appetite, although every one of them must have known that it would be impossible to satisfy it by the sight of the execution. This large crowd stood there in the street and upon the sidewalks, as near to the steps leading to the jail entrance as the lines of policemen, drawn up to make a clear passage-way for all who had permits, would permit them to come, and they held the place from two or three hours before the execution until it was all over. They could do no more than look up at the walls of the prison, or watch the going and coming out of those who were permitted to do either. They could see nothing whatever of the scenes inside, nor hear anything, except that which those who at last passed out told them. Yet there the multitude remained eagerly watching for any sign that might afford them information of the progress inside the jail toward the awful end, and meanwhile they indulged in rough jokes and unfeeling remarks. Many tarried until the coffined corpse of Chin Mook Sow was brought out and the wagon in which it was placed had been driven away. And even then the place seemed to have an overpowering fascination for them, as they slowly walked away and would stop and turn and look back upon the prison. . . . Between two hundred and three hundred persons, all told, were admitted on the occasion.

-- The San Francisco Examiner, May 5, 1877

Seven years later:

Sheriff Connolly gave orders to admit those who had permits. The possessors of these black-bordered sheets of notepaper had been clamoring for admission for an hour. The Sheriff had issued invitations to 400 persons, all the jail would hold, and there were at least 4,000 more hunting him high and low all over the town during the past two days seeking passes. So great was the clamor that the official has been obliged to keep himself locked up in jail for about forty-eight hours. The telephone in the Captain’s room was kept tinkling all morning by people who had discovered that they had been forgotten. Seven messenger boys at one time stood on the front steps with notes to the Sheriff requesting permits.

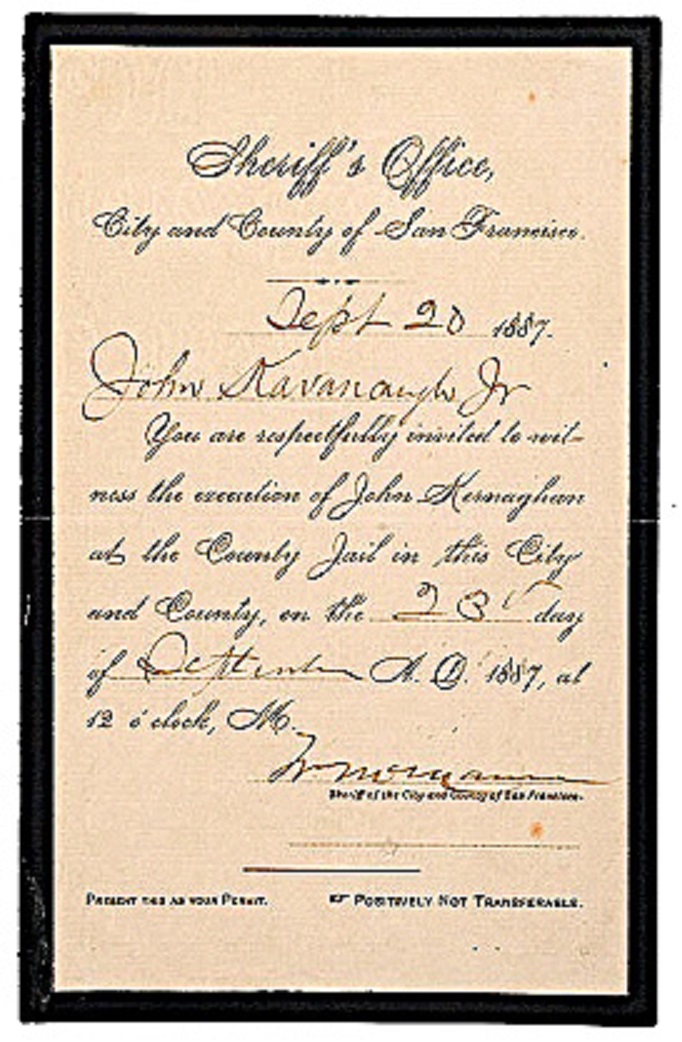

Sheriff William McMann sent this invitation to one John Kavanaugh Jr. to witness the execution of convicted murderer John Kernaghan at the Broadway Jail on September 23, 1883.

-- The San Francisco Examiner, Sept. 13, 1884

Sometimes the Sheriff went overboard in issuing invitations which attracted hundreds of spectators and lead to a complete breakdown of the entire execution process. As in the case the 1888 execution of Alexander Goldenson. The San Francisco Examiner provided a vivid report on the chaos that followed:

Sheriff McMann erred on the side of generosity in the manner of distributing passes to the execution. There was also some lack of discrimination in the selection of the recipients. As a consequence the capacity of the jail was overtaxed, many with tickets were unable to get in, and the crowd was one of the noisiest and most turbulent that ever thronged Broadway in front of the old jail.

The experiment of holding the Sheriff’s guests back until an hour before the execution also proved unfortunate, for there proved so many of them that the experienced ones promptly recognized the fact that the jail’s capacity was not equal to containing all, and began to make a fight for a position to command the jail steps when the ticket-takers put in an appearance. Their movement started the remainder of the crowd, and by 11 o’clock there was a brawling, sweating, swearing, yelling, laughing mob of 1,500 men, fighting shoulder to shoulder, every man against his neighbor, to advance toward a common goal – a commanding view of the death of a murderer.

-- The San Francisco Examiner Sept. 15, 1888

The newspapers of the day often decried the very existence of the death penalty, but the headline writers had no room for sympathy in their pithy headlines. Headlines often referred to the method of execution being by hanging: “Sing Swings,” or, “Swung Off.” Sometimes they were much more hostile: “The Thug to Die.” (George Wheeler, 1884, Examiner), or cruelly descriptive: “Another Dull Thud.” (Alexander Goldenson, 1888, Sacramento Daily Record-Union).

Not all condemned men were willing to wait for the Sheriff’s noose. Several men scheduled for execution committed suicide on the eve of their date with the gallows.

George Colmere used a comb tooth to open a vein on February 5, 1864, the night before his execution. Five years later, in April 1869, Ah Kow hung himself in this cell rather than face the death penalty. And, in spite of precautions to prevent such suicides, on March 2, 1883, Sing Lum hung himself in his cell on the night before he was to be hung after asking the deputy assigned to watch over him to fetch them both some tea. Tragically, that deputy sheriff died of a heart attack in the jail within a few hours of the suicide.

Executions In San Francisco: Pre-1850

Francisco Rubio, a Hispanic soldier, was executed by firing squad in 1831 for murder-rape. This execution is noted in Bancroft’s Popular Tribunals, Vol. 1, p. 745.

Executions In San Francisco: 1850 to 1890

Jurisdictional note: In 1856, the voters approved The Consolidation Act, which merged the City with the County of San Francisco. Until that time, they were two separate jurisdictions, with the Sheriff in charge of the jail, court security and the outlying area of the county. He was considered a County official. There was a set of elected City officers, usually including the City Marshall (later Chief of Police), Aldermen, Mayor, etc. The city was basically the upper east half of the peninsula, with the western city line about where Buchannan Street is today going south to Mission Dolores and then east to the Bay. The rest of the peninsula, all the way down to Santa Clara County, was part of San Francisco County. San Mateo County was formed south of San Francisco in 1856, the same time as the consolidation of San Francisco City & County.

A “Committee of Vigilance” was formed in San Francisco on two separate occasions, in 1851 and again in 1856. In each instance the Vigiliance Committee completely overtook San Francisco's existing criminal justice system as the vigiliantes had their own own jail, court hearings, criminal trials, and punishments. The two Committees publicly executed eight individuals.

In the following list, the letter “V" indicates executions committed by one of the two Committees of Vigilance which were formed at different times between 1851 and 1856 in San Francisco. The letter "S" indicates a lawful judicial execution by the San Francisco Sheriff. The names of the Sheriffs in office when the executions occurred are noted.

There were 18 legal executions and 8 illegal/vigilante executions conducted in San Francisco between 1850 and 1890:

Sheriff John C. Hays: elected Sheriff on April 1, 1850. Reelected September 3, 1851; served until June 17, 1853.

V-1 John Jenkins June 11, 1851. Hung. Committee of Vigilance (COV).

V-2 James Stuart July 11, 1851. Hung. Committee of Vigilance.

Neither John Jenkins or James Stuart were ever in the county jail prior to being hanged. Jenkins was “arrested” by a group of citizens who caught him stealing a safe. They turned him over to the newly formed COV, who “tried” him, sentenced him and hung him in about 6 hours. Stuart was also “arrested” by a group of citizens (on July 2nd) and turned over to the COV. He was tried, sentenced and hanged 9 days later.

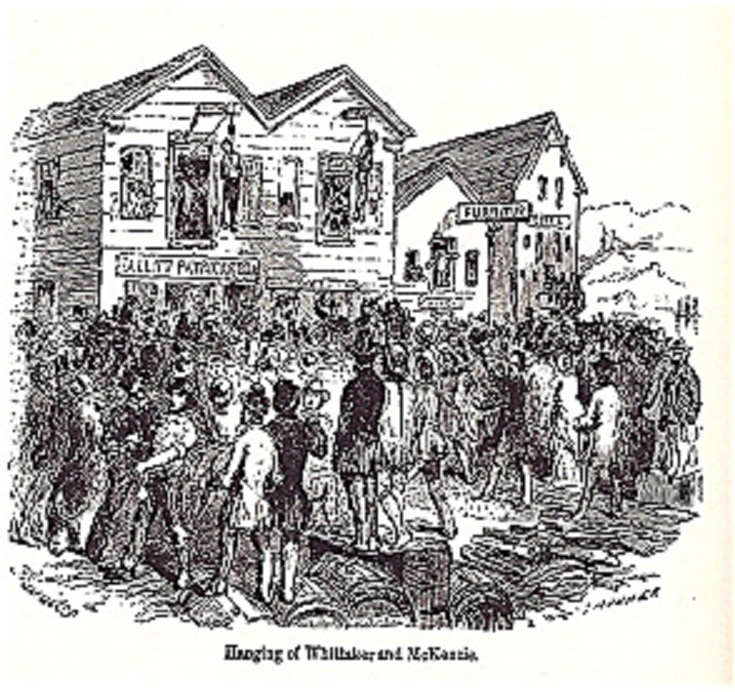

V-3 Robert McKinsey August 24, 1851. Hung. Committee of Vigilance.

V-4 Samuel Whittaker August 24, 1851. Hung. Committee of Vigilance.

McKinsey & Whittaker were “taken” from the county jail on Sunday, August 24th by the COV while Sheriff Jack Hays was away from the jail at a bullfight, most likely lured away, “wittingly or unwittingly” as historian Kevin Mullen states in Let Justice Be Done. The two men had been arrested by the COV and held in COV headquarters. Sheriff Hays was ordered to bring them to jail, so on August 19th, the Sheriff, his deputy John Caperton, Mayor Brenham and the Governor, John McDougal, all went to the headquarters, forced themselves in and took custody of the two men. The COV took them back five days later and hung them.

S-1 Jose Forni (aka Jose Forner y Brugada)

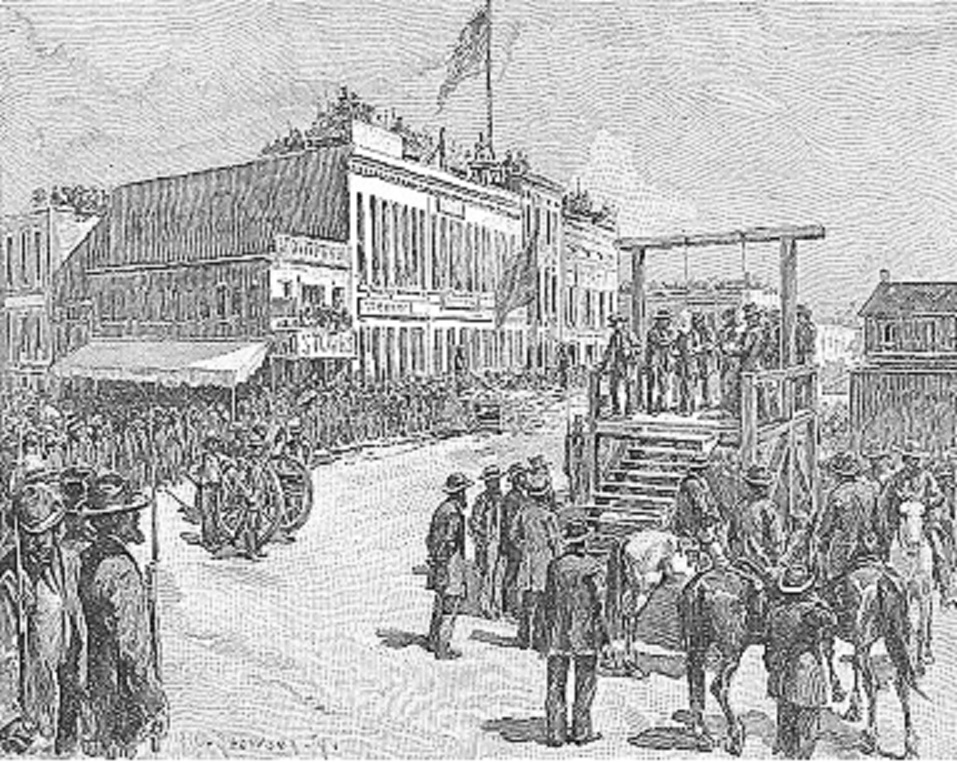

December 10, 1852, a Hispanic man hung for the stabbing murder of Jose Rodriguez. This is the first official or legal hanging in San Francisco. It was witnessed by thousands of people who gathered around the scaffold on Russian Hill. (Museum of San Francisco. www.sfmuseum.org/hist9/forner). Mr. Forni confessed to his murder and the confession was printed on a lettersheet” along with a drawing of Forni sitting in his cell. “Published under the direction of the keepers of the County Jail and for sale by Bonestell & Williston, Clay Street. San Francisco.” The lettersheet is reproduced at the S.F. Museum website. This execution is also the subject of a detailed drawing of Forni on the gallows surrounded by a huge crowd. Sheriff Hays officiated at this hanging. According to his biography: Colonel Jack Hays, Texas Frontier Leader and California Builder, 1952, p. 286, “Sheriff Hays . . . cut the rope which upheld the ‘drop’”.

Sheriff William Gorham: elected Sheriff, September 4,1853; served through September 5, 1855.

S-2 William B. Sheppard

July 28, 1854. Hanged on “Government Reserve property” close to the Presidio in the presence of 10,000 people. He had stabbed to death Henry C. Day. Sheppard had worked for Day and hoped to marry Day’s daughter. When Day forbid the marriage, Sheppard stabbed Mr. Day several times. This execution and that of Jose Forni were the only lawful public executions to take place in San Francisco. Sheriff William Gorham officiated over the execution. Details of this execution are found in the Daily Alta California newspaper July 27-28-29, 1854. According to The Alta, Sheppard was allowed to hang for one hour before being cut down. See also: A Tale of Old San Francisco - A Historical Account of the Tragic Life of William B. Sheppard, Edgar Smith, Sejanus Press, 1998.

Note: Felipe Alvitre is listed as an SF execution in various places, but this execution actually took place in Los Angeles on January 12, 1855. See story in Bancroft’s Popular Tribunals, p. 495.

Sheriff David Scannell: elected on September 5, 1855; served through September 4, 1857.

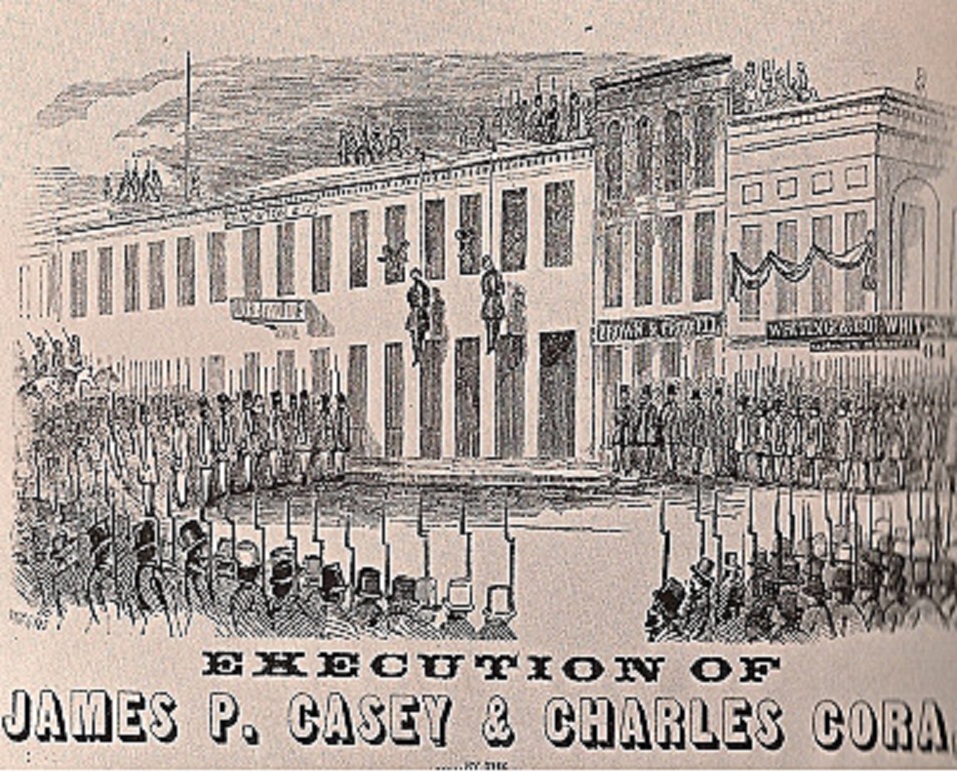

Scannell’s term in office was one of the most controversial, as the Committee on Vigilance of 1856 took two prisoners (Cora & Casey) from the jail on Broadway and hung them, believing that the local authorities would not secure a conviction or impose punishment. Toward the beginning of his time in office, in April 1856, the City and the County were “consolidated” by State legislation, making David Scannell the first “Sheriff of the City and County of San Francisco.” Scannell moved executions from the public into the yard of the county jail on Broadway Street.

V-5 Charles Cora

May 22, 1856. Hung by the Committee of Vigilance for the murder of Federal Marshal William Richardson. Cora allegedly shot Richardson because Richardson had insulted Cora’s lover, although Cora claimed the shooting was in self-defense.

V-6 James P. Casey

May 22, 1856. Hung by the Committee of Vigilance for the murder of James King of William. Casey was a member of the Board of Supervisors. James King of William was the Editor of The Daily Evening Bulletin who had exposed Casey’s past criminal record.

S-3 Nicholas Graham

May 30, 1856. Hanged in the yard of the County Jail on Broadway for having stabbed to death a shipmate, Joseph Brooks, on 1-18-1856. Graham admitted the stabbing, but blamed his actions on liquor.

Sheriff David Scannell conducted the execution. This execution is noted in Annals, Vol. 1, p. 748, and elsewhere as taking place on May 2, 1856, but on May 1st Graham received a Governor’s reprieve until May 30. Graham was executed by the Sheriff in front of about 100 witnesses on May 30, 1856. Details of this execution are found in the Daily Alta California, May 28-31, 1856. Notice of the Governor’s reprieve is in the Daily Alta California on May 1, 1856.

Vigilantes conducted a double hanging on July 29, 1856. Philander Brace and Joseph Hetherington, who were never arrested or tried, were executed for murder.

July 29, 1856. Hung by the Committee of Vigilance, for the murder of Joseph. B. West.

V-8 Joseph Hetherington

July 29, 1856. Hung next to Brace by the Committee of Vigilance for the murder of Dr. Andrew Randall and a Dr. Baldwin. Neither Brace nor Hetherington was in the custody of the sheriff prior to their execution. Brace had earlier been “banished” from San Francisco for a year old murder, but came back and was pinched in a pub in June by COV members who recognized him. He was taken to COV headquarters, tried on July 16th, hung along with Hetherington on July 29th. Hetherington, also having committed an earlier murder (in 1853) got in a shoot out with a physcian on July 24th. He was immediately arrested by a police officer, but the cop was persuaded to turn him over to the COV rather than taking him to a station house. Hetherington was tried two days later and hung 5 days after the arrest.

Sheriff Charles Doane: elected September 4 1857; served through October 7, 1861.

Doane had been the Grand Marshall of the Committee on Vigilance, which made him the head of their armed units. He was one of the highest ranking members of the COV. In 1856, he led the armed takeover of the county jail to take custody of Cora and Casey prior to their hanging. He was formally elected Sheriff in 1857 and reelected in 1859.

S-4 Henry F. N. Meuse (aka Charles Douse)

December 10, 1858. Hung. Muese stabbed Peter Becker to death on June 4, 1858 and robbed him of one hundred dollars. Deputy Sheriff Ellis read the death warrant as the prisoner stood on the trap door. “The culprit was neatly dressed in a white shirt, brown pants, black frock coat, black satin vest and black cravat.” Alta, 12-11-58. His body was allowed to hang for 30 minutes before being placed in a coffin. The execution took place in the Broadway county jail yard.

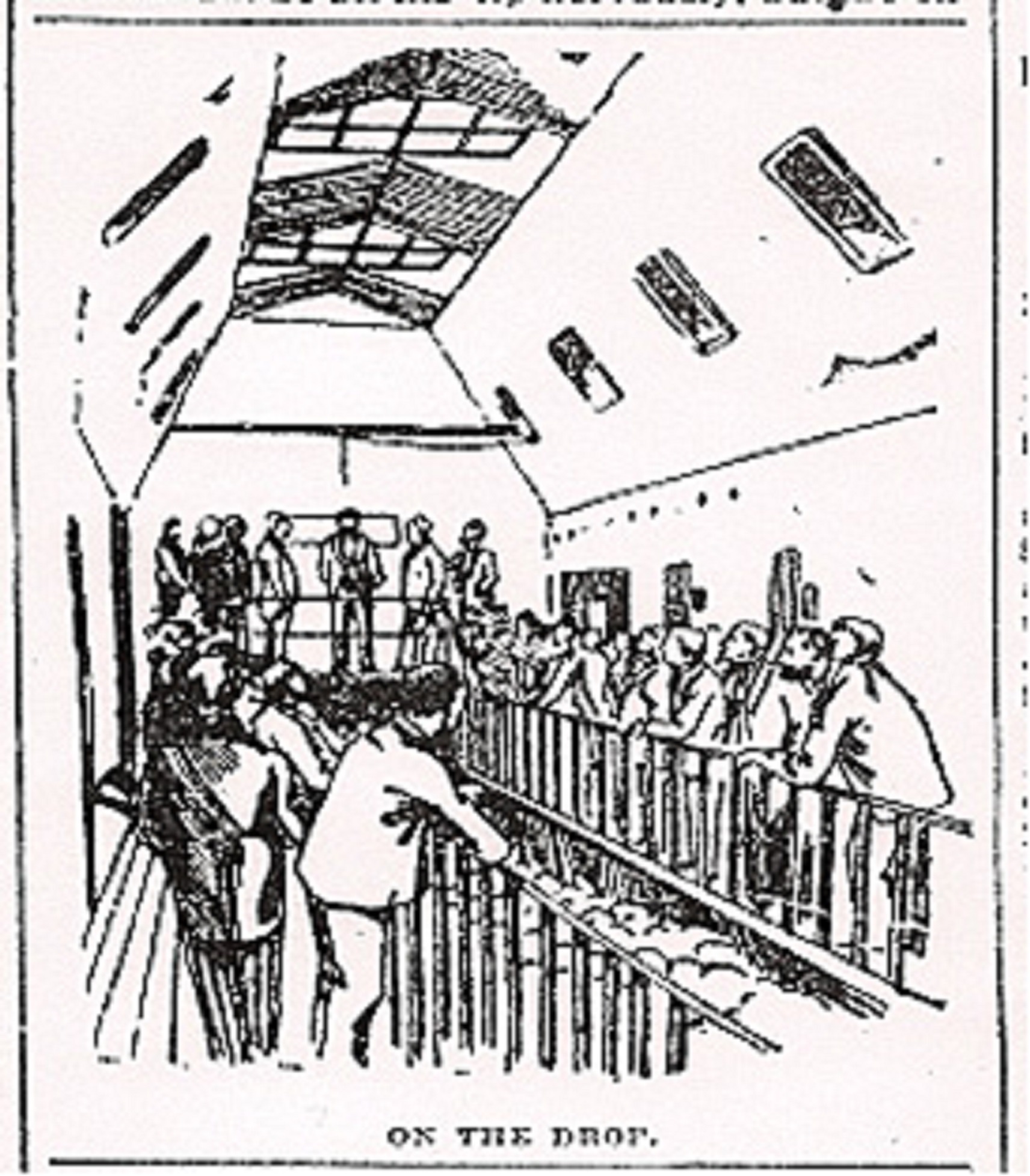

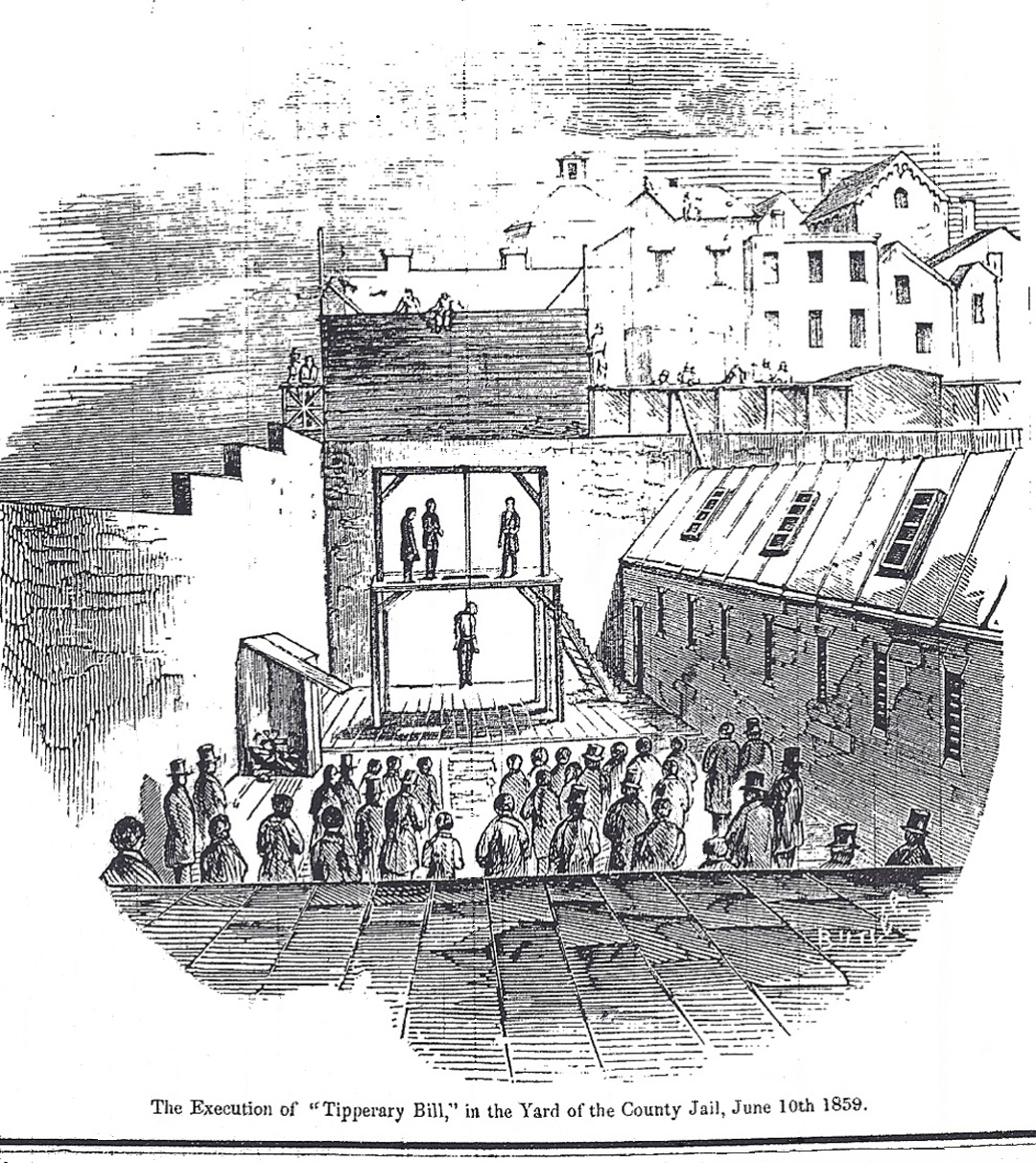

A rare view of the Broadway Jail's rear "yard" where many of San Francisco's legal executions were held. This is the June 10, 1859 hanging of William Morris (aka Tipperary Bill).

S-5 William Morris (aka Tipperary Bill)

June 10, 1859. See drawing at right showing the Morris execution in The Evening Bulletin of June 10, 1859. Hung for the shooting death of Richard K. Doak on November 19, 1858, during a barroom dispute. The execution took place in the Broadway Jail yard. A drawing of this execution appeared in California Police Gazette.

S-6 James Whitford

The execution was on September 21, 1860, also in the jail yard. Hung for having shot Edward Sheridan on February 1, 1860, over a pay dispute.

S-7 Albert Lee

African American. March 1, 1861. Hung for having murdered his estranged wife, Madelaine Delphine Aggie Pullier Lee, on July 3, 1859, because she would not reconcile with him. He then attempted suicide. Sheriff Doane oversaw this execution in the jail yard.

S-8 John Clarkson

African American. June 4, 1861. Hung in the jail yard. For the murder of his estranged lover, Caroline F. Park, by cutting her throat with a razor on December 1, 1860.

Sheriff John Ellis: elected on 9-21-1861. Assumed office 10-7-1861 (San Francisco Municipal Reports, 1861-1862).

Re-elected on May 19, 1863 and assumed office for his second term on July 1, 1863, per The San Mateo County Gazette, www.sfgenealogy.com. Resigned sometime before 6-1-1864, probably May 1, 1864. His Undersheriff was Henry Davis, who finished Ellis’s term when Ellis resigned. Davis then successfully ran for election in his own right. Sheriff Ellis did not execute anyone.

Note: Edward Bonney (aka Frank Bonney) hung May 9, 1862 for murder. This execution is sometimes noted as a San Francisco event, but the execution actually took place in San Leandro. Bonney killed a San Francisco man, but the trial took place in San Leandro and the execution took place in San Leandro on 5-9-1862 (Alameda County).

Sheriff Henry Davis: in the Municipal report for FY 1863-1864, Davis stated, “I assumed the office of the Shrievalty on the 1st of June 1864, to fill the unexpired term of Mr. John S. Ellis, resigned.”

It is clear from The Daily Alta California that Henry Davis ran for election for the post of Sheriff in the election of May 17, 1864, as a candidate of The People’s Party, and won by a healthy margin against one opponent, Charley Weller of the Copperhead party. This was a “special” election, to fill the post vacated by Ellis.

Reelected on May 16, 1865, putting the Sheriff elections back on the regular two-year schedule. Sheriff Davis lost the election on September 4, 1867 to P.J. White. Sheriff Davis changed the execution protocol, moving the gallows to inside the Broadway jail building. All future executions were performed in this location.

S-9 Barney Olwell

January 22, 1866. Hung for shooting and killing James Irwin on January 13, 1865. Irwin, a farmer, owed Olwell $40, but could not pay him, so Olwell shot him.

S-10 Antonio Sassovich

April 28, 1866. Hung for the stabbing murder of Edward Walter on June 3, 1865. Sassovich felt he had been laughed at and insulted by Walter.

S-11 Chung Wang (aka Chu Wong)

July 6, 1866. The first person of Chinese descent to be hung for murder. Wang stabbed his mistress to death when she left him for another man.

S-12 Thomas Byrnes

September 3, 1866. Hung. For the murder of Charles P. Hill in February 1865, during the course of a robbery.

Sheriff P. J. White: elected September 5, 1867.

Ran against the incumbent, Henry Davis, took office mid FY 1867-68, re-elected 5-16-1869. Served until September 4, 1871. Sheriff White did not execute anyone.

Sheriff James Adams: elected 9-4-1871.

Served one term in office until September 3, 1873.

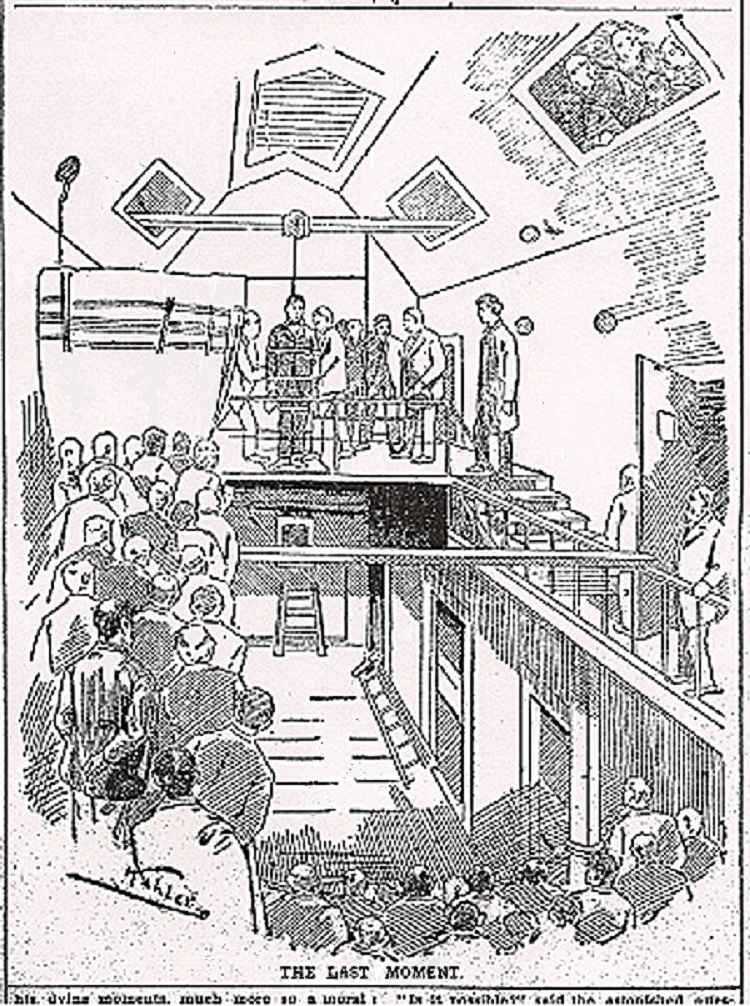

The following are a series of three extraordinary graphic drawings from the San Francisco Examiner showing the legal executions of three condemned murderers inside the Broadway Street County Jail. At some point the executions at the Broadway Jail were moved from the rear outside jail yard to inside the jail on the second story. This is the November 19, 1886 hanging of Fong Ah Sing.

S-13 John Devine (aka Chicken Devine)

May 14, 1873. Hung. For having shot and killed August Kamp during a robbery (see lengthy story about Chicken Devine in Shanghaiing Days, by Richard Dillon,1961). The execution took place inside the Broadway jail.

S-14 Charles Russell

July 25, 1873. Hung for the murder of James Crotty. Russell shot Crotty in the head. Russell’s only defense was that he was drunk at the time.

Sheriff William McKibbin: elected 9-3-1873.

Defeated in reelection bid on September 5, 1875. Did not execute anyone.

Sheriff Matthew Nunan: elected September 5, 1875.

Re-elected 1877, served until September 3, 1879.

S-15 Chin Mook Sow

May 4, 1877. Hung for the stabbing murder of Ye Ah Chin over a money dispute. Sheriff Matthew Nunan oversaw Sow's execution inside the Broadway Street county jail.

S-16 John Runk

April 26, 1878. Runk was barely 18 when executed. Hung for the having shot to death police officer, C. J. Coots, exactly one year after the date of the crime. Coots had arrested a friend of Runk’s, and Runk shot the officer to allow his friend to escape. The execution did not go well, with Runk “writhing” for quite some time before dying. According to The Alta, “The noose was so carelessly adjusted that his neck was not broken. He struggled terribly, and it was fearful to witness his contortion. His chest heaved, and the gasps could be distinctly heard. Nine minutes after he dropped, he gave his last gasp.” (Alta, 4-27-78).

Sheriff Thomas Desmond: elected September 3, 1879.

Defeated in reelection bid on September 7, 1881. Did not execute anyone.

Sheriff John Sedgwick: elected September 7, 1881.

Defeated in reelection bid one year later, November 7, 1882. Did not execute anyone.

Sheriff Patrick Connolly: elected November 7, 1882.

Served until November 4, 1884. Did not seek reelection.

S-17 George Wheeler

January 23, 1884. Hung for the murder by strangulation of his sister-in-law, Delia Tillson, who was attempting to break off an affair with Wheeler.

S-18 Frank Hutchings

September 12, 1884. Hung for the murder by strangulation of Jeanette Simms because she was leaving him for another man.

Sheriff Peter Hopkins: elected November 4, 1884.

Served until November 6, 1886. Did not seek reelection.

S-19 Wright Leroy

January 16, 1885. Hung inside the county jail for the murder of Nicholas Skerrett. Leroy strangled Skerrett and then attempted to transfer all of Skerrett’s considerable assets to himself. Sheriff Peter Hopkins conducted the execution on his second week in office.

S-20 Stephen Jones

African American. March 20, 1885. Hung for the murder of his former lover, Agnes Riley. Jones shot her several times and then attempted to shoot himself, but failed. The execution took place inside the Broadway county jail.

S-21 Fong Ah Sing

November 19, 1886. Hung for the murder of Choy Cum, a Chinese courtesan, on October 18, 1881. Choy Cum had spilled water on Fong, so he shot her. The execution took place inside the Broadway county jail. A drawing, shown below, depicting the execution appeared in The Examiner on November 20, 1886.

Sheriff William McMann: elected November 6, 1886.

Served until November 6, 1888. Did not seek reelection.

Saloon owner. Execued on September 23, 1887. Kernaghan was hung for the murder of his sister-in-law, Martha Hood. Kernaghan felt she had humiliated him by exposing his financial troubles and incompetence. He beat her to death with a hammer. A drawing of the execution entitled “On The Drop” (left) appeared in The San Francisco Examiner on September 24, 1887.

S-23 Sare Bo Lee

September 30, 1887. Hung for the murder of Chu Ah Chuck on October 3, 1882. Chuck was ambushed by two gunmen in the heart of Chinatown, likely in retaliation for his cooperation with police authorities.

The murder of Chu Ah Chuck was part of the Tong Wars that seared through San Francisco's Chinatown from the early 1880s through 1921. Sare Bo Lee Lee protested his innocence throughout his trial, and continued his last minute pleas as he stood on the gallows. Many citizens including the Chief of Police and the former District Attorney unsuccessfully sought clemency for him.

S-24 Alexander Goldenson

September 14, 1888. Hung for the shooting murder of 14 year old Mary Kelly on November 10, 1886. It was a sensational crime and trial, including an attempt to lynch Goldenson and his attempt to take his own life in the jail with poison. Goldenson was 18 at the time of the murder. He had a crush on Kelly and she rebuffed him. He held a photo of Mary Kelly and an American flag in his hands as he was hung. The drawing below, from The Examiner, shows the crowded conditions and curious onlookers peering through the jail’s skylights.

S-25 Leong Sing

December 28, 1888. Leong Sing was hung in the Broadway county Jail for the murder of his uncle, Leong Chun, in Chun’s restaurant at 830 Washington Street on March 30, 1877. The uncle was treasurer of the Leong Si Tong and the murderer wanted his five dollar membership fee returned. When the uncle refused, Sing shot him three times. The execution was one of the last official acts of Sheriff William McMann. The next sheriff, Charles Laumeister, had already been elected, but had not yet assumed office. Nevertheless, Sheriff-elect Laumeister attended the execution, along with his new Chief Jailer, Michael Smith, and his new Undersheriff, Peter Deveney.

Sheriff Charles Laumeister: served from 1889-1892.

S-26 Wong Ah Hing (aka Ah Tee)

February 14, 1890. This was the last execution to take place within San Francisco. Future executions of San Francisco criminals would take place in the State Prison in San Quentin. Wong Ah Lee stabbed his uncle, Wong Ming See, to death. The killer had felt humiliated by his uncle, but little more contributed to the murder.

Legislation was passed in 1891 redirecting all California executions to the State Prison. The first State Prison execution took place in San Quentin Prison on March 3, 1893 when Jose Gabriel, a Native American, was hung for a murder that took place in San Diego county.

Several California sheriffs still conducted a small number of executions after this date (of criminals convicted and sentenced before the law changed), but the era of executions conducted by individual California counties was effectively over after 1891.

-------------------------------------------------

Sources: in all executions noted, all dates have been verified through contemporary newspaper accounts, primarily The Daily Alta California, The San Francisco Call, The Daily Evening Bulletin and The San Francisco Examiner. Other sources include:

(1) Legal Executions in California. Sheila O’Hare, Irene Berry & Jesse Silva. McFarland & Co., North Carolina (2006). This is the definitive registry of all California executions, 1850-2005.

(2) A database of all California executions as compiled by Rob Gallagher, or by “Executions in the United States, 1608-1987: The ESPY File,” Espy, M. Watt and Smykla, John Ortiz. This study was funded by The National Science Foundation. The compilation is reasonably accurate, but contains several errors as to dates and fails to note certain executions. Other sources, including contemporary newspaper accounts have been used to correct errors in this listing. http://users.bestweb.net/~rg/execution.htm

(3) “A Record of Legal Executions in California,” http://sfgenealogy.com/sfhistory/hghan.htm. Helpful, but incomplete.

(4) Museum of San Francisco: http://www.sfmuseum.org.html.

(5) San Francisco Municipal Reports. (SFMR). Beginning at least by FY 1860-61 the Sheriff filed an annual report, many of which displayed a month-by-month summary of significant activities, including how prisoners were “disposed of.” One of the categories noted is “Executed.” Sheriffs Nunan & Laumeister did not note their executions.

(6) Popular Tribunals, Vols. I & II, Bancroft, 1877.

(7) Colonel Jack Hays, Texas Frontier Leader and California Builder, James Kimmins Greer, W.M. Morrison Pub, Waco, Texas 1952.

(8) A Tale of Old San Francisco: A Historical Account of the Tragic Life of William B. Sheppard. Edgar H. Smith, Sejamus Press, Reno, 1998.

(9) The Lion of the Vigilantes: William T. Coleman. James A. B. Scherer. Bobbs-Merrill Co. New York, 1939.

(10) Let Justice Be Done. Kevin J. Mullen, University of Nevada Press, 1989.

(11) Dangerous Strangers: Minority Newcomers and Criminal Violence in the Urban West, 1850-2000. Kevin J. Mullen. Palgrave MacMillan. 2005.

(12) San Francisco’s Mayors 1850-1880. William F. Heintz, Gilbert Richards Publications, 1975.

(13) San Francisco As It Is, Being Gleanings from the Picayune, 1850-1852. Kenneth M. Johnson, Talisman Press, 1964.

(14) Shanghaiing Days. Richard H. Dillon, Coward-McCann, Inc., 1961.

(15) History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851. Mary Floyd Williams, Da Capo Press, 1969.

(16) California From the Conquest in 1846 to the Second Vigilance Committee in San Francisco. Josiah Royce. Alfred Knoph. 1948.

(17) The Annals of San Francisco and History of California, Frank Soule, John Gihon & James Nesbet, 1855, reprinted in 1966 by Lewis Osborne, Palo Alto.

(18) City of the Golden ‘Fifties. Pauline Jacobson. University of California Press. 1941.