Thomas P. Johnson served the shortest term as Sheriff in the history of the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department, a mere 80 days in 1853. He had been a Deputy Sheriff under John Coffee Hays, the City’s first elected Sheriff who took office in 1850 when California became the 31st State.

Hays resigned in August of 1853, several months before his second two-year term as Sheriff was to set to expire, to accept an appointment as Surveyor General of California, and Johnson was appointed to replace him.

Despite being chosen to finish off Hays’ second term of office, and having close ties to the beloved Hays, Johnson immediately ran into several political buzz saws. Though he sought election to the office twice, he was defeated both times. After his second defeat, in 1855, Johnson permanently returned to his home state of Kentucky to live the life of a farmer.

Thomas P. Johnson grew up in Georgetown, Kentucky and, by one account, was the nephew of George Washington Johnson who was the first Confederate governor of Kentucky.

In 1847 Johnson joined thousands of other newly minted miners who trekked to California chasing wealth and a new life during the great Gold Rush. After apparently not finding digging in the gold country to his liking, Johnson ended up in San Francisco where he was hired by Sheriff Jack Hays to be one of the very first appointed deputy sheriffs in Department history.

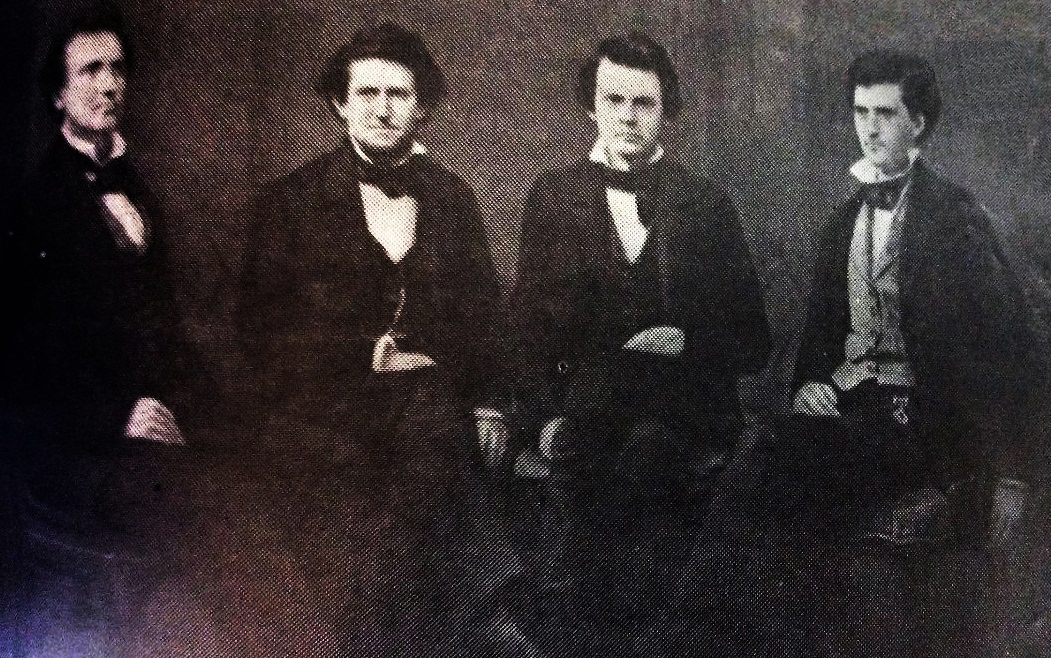

A photo probably taken in 1853: Sheriff John Coffee Hays (second from left) poses for the camera with three of the first San Francisco Deputy Sheriffs hired in the Department's history.

From left: Undersheriff John Caperton, Sheriff Hays, Deputy John Freaner, and Deputy Thomas Johnson. Caperton was originally a Major in Jack Hays' Texas Rangers outfit and they shared many adventures and close calls on the Lone Star frontier in the 1840s. In January 1850, after they completed an assignment for the newly created Federal Department of the Interior, Caperton joined his best friend Hays on an epic journey to San Francisco.

Other Deputy Sheriff's listed in City directories from 1850 to 1853 are Dep. B. F. Harley, Dep. Thomas Hayes, and Dep. John L. Powers.

The Alta highly approved of Johnson’s appointment stating, “Mr. Johnson, the new Sheriff, is a young man, who has been in the office for some time, and has the reputation of being a faithful and attentive officer.” Thomas Johnson took office as San Francisco’s second Sheriff on June 17, 1853.

Although Sheriff Thomas Johnson’s time as Sheriff was brief, it was not uneventful.

Almost immediately, Johnson was thrust into a heated taxation controversy. A state-imposed tax of sixty cents per one hundred dollars was being imposed on “consigned” goods. San Francisco was the major port of import for the West Coast, and many profitable San Francisco businesses took items from ships “on consignment,” with the profit from sales to be split between the “consignment house” and the owner of the goods.

The local merchants contested this new tax, and it was a tax that Sheriff Johnson was called upon to enforce. On July 1, 1853 Johnson held a meeting with a dozen of the most prominent local merchants to “answer to the formal interrogatory whether they would pay the tax, they unanimously responded in the negative.”

According to the Alta, the business owners were then placed under arrest. The businessmen were eventually released from custody and the matter was sent to the California Supreme Court for a ruling.

The Court’s ruling came in January of 1854, with the state tax being upheld (People v. Coleman, 4 Cal. 46,1854).

Another great controversy of the day mirrors a similar modern-day big-city issue in America: the phenomenon of homeless people taking over and living on public land. In the 1850s they were called “squatters” and they could be found in abandoned structures, tents or simply living in the open on public and private land holdings throughout San Francisco.

Reflecting a segment of homeless advocacy in the 21st century, there was a feeling among many in mid-nineteenth century San Francisco that any unoccupied land could be open to becoming “public land,” or land that was free to be claimed by anyone who was willing to live on it and erect a structure.

As a result, aggressive squatters began claiming both public and private property all over San Francisco. They erected tents, fences and even buildings on these “unclaimed” properties. The rightful owners of the property were not amused and physical conflict was often the result, as noted in this July 17, 1853 Alta newspaper report:

“There has been for the last week quite a lively time in the suburbs, among the squatters and those who consider themselves the ‘Lords of the Manors.’ Yesterday, at the ‘Lagoon,’ muskets were bro’t into the field, but no more serious damage done than the flowing of a little ‘claret’ by assault with the knuckles.”

Unfortunately, the violence escalated later that month resulting in a shootout involving one of Sheriff Thomas Johnson’s staff, Deputy John Freaner.

The situation was typical; the result was not. As the Alta reported, a property owner named Robert Price obtained a court order to “eject” a squatter named Redmond McCarty from property Price owned at Second and Mission Streets. On July 20, 1853, Deputy Sheriff McMeans went to the property to take possession of it and expel McCarty from a structure at the site.

McCarty informed Deputy McMeans that he would not leave and, further, he would shoot anyone who tried to remove him from the property. Deputy McMeans left and returned to the Sheriff’s office for additional help.

Less than two hours later, Deputy Sheriff John Freaner joined Deputy McMeans and they went back to the property to confront McCarty. Freaner, who was unarmed, and McMeans entered the structure at Second and Mission and Freaner identified himself as an officer of the law and presented McCarty with the removal court order. Whereupon McCarty presented Freaner with a Colt Navy revolver pointed inches from his chest, and promised to shoot him and anyone else who tried to remove him. The two Sheriff’s deputies turned and left the structure and McCarty slammed the door shut behind them.

Deputy Freaner immediately asked about for a gun and was handed a small five shot revolver. Freaner went back to the front door and attempted to kick it in, knocking out several panels. McCarty shot through the door hitting Freaner in the hip, and the gunfight was on. Deputy Freaner fired back at McCarty, who returned fire several times as he retreated to back room. Freaner unloaded his five shooter toward McCarty, hitting him twice and seriously wounding him, and the shootout ended.

Deputy Freaner walked away from the structure, mounted his horse and, against the advice of those who urged him to wait for a carriage, rode to his home to take care of his wound. Freaner’s gunshot wound healed but McCarty’s were said to be “dangerous”; it is not known if he survived the encounter.

David Broderick was born in Washington D.C. in 1820, and his parents moved the family to New York City in 1823. After attending public school Broderick became an apprentice stone cutter and also became active in the Democratic Party. At the age of 26 he ran for a New York congressional seat and lost but remained politically active his whole life.

In 1849 Broderick came to San Francisco as part of the transcontinental Gold Rush, one of his traveling companions being future San Francisco Sheriff William McKibbin. Broderick did well in business and was elected to California’s State Senate and eventually appointed a US Senator by the State Legislature (popular election of senators did not begin until 1912 when the 17th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified).

Throughout the history of the Sheriff’s Department, the fate of a number of incumbent San Francisco Sheriffs, and candidates running for the office of Sheriff for the first time, was often fully dependent on local party strength. It was not uncommon for a Sheriff to win or lose a given election as part of a general party sweep of a number of elective offices. Such was the fate of Sheriff Thomas Johnson.

California Democrats held their first organizing meeting in Portsmouth Square on October 25, 1849, just over five months before California was to become a State. John Geary, who became San Francisco’s first Mayor after the City was incorporated, organized the meeting and emerged as an early Democratic leader.

Possibly the most controversial Democrat of the time was David Broderick. Broderick was a product of New York’s Tammany Hall politics, who came to San Francisco in 1849 and was elected to the State Senate in 1850. For the next nine years, until his death in a duel in 1859, Broderick ruled the anti-slavery wing of the state and local Democratic Party, often with underhanded tactics such as ballot stuffing and voter intimidation.

Prior to the September 1853 General Election, newspaper accounts at the time left little doubt that Thomas Johnson emphatically wanted the position of Sheriff and he campaigned very hard to get it.

Johnson was considered a legitimate candidate by attendees of the Democratic convention held before the election, even though he had apparently told convention members that he would not accept the Democratic nomination. It’s likely that Johnson’s Kentucky background put him at odds with the anti-slavery wing of the Democratic Party.

Johnson ran as an independent and placed an advertisement in the local papers declaring his candidacy and seeking the support of San Francisco voters.

He was a favorite of the Alta California who considered him to be the only truly qualified candidate. And, while party politics were still in their infancy in San Francisco, many independent organizations sprung up at election time to take positions and endorse candidates.

Johnson was endorsed by a group calling themselves the “Regular Mechanics’ and Workingmen’s Ticket.” He was also the candidate of choice for a group called the “Anti-Extension Reform Ticket” who were formed largely to oppose to a giveaway of state-owned lands to developers. Although these “independent” political groups were formed around specific issues, it is notable that both organizations also endorsed the Whig candidate for governor, William Waldo.

Johnson’s main opponent, a local baker and militia leader named William Gorham, was ultimately the chosen candidate of the Democrats, who were also endorsing incumbent John Bigler for reelection as Governor. Other candidates for Sheriff included George Hossefross of the Independent Party, and another Democrat named Nathaniel Blackstone.

When the September 4th election votes were counted, the Democrats maintained a slight edge in San Francisco. San Francisco voters favored Bigler slightly over Waldo for Governor (5,480 votes to 5,475), and greatly favored Democrat Gorham over incumbent Sheriff Johnson, by a count of 4,942 to 3,073.

Although the two other candidates for Sheriff, George Hossefross (2,857 votes) and Nathaniel Blackstone (24 votes), probably took more votes from Johnson than from Gorham, Johnson would have needed to get at least 83% of the other two candidates’ combined votes to beat Gorham—an unlikely scenario.

Thomas Johnson remained in San Francisco for several years, although he traveled back to Kentucky in 1854 where he married Laura Miller. Johnson brought his new wife back to San Francisco where their first child was born, in 1855. They named the child “Freaner,” no doubt a tribute to Johnson’s former deputy John Freaner.

Thomas Johnson ran for San Francisco Sheriff a second time in 1855 after incumbent Sheriff William Gorham chose to not seek reelection. Johnson, who was now affiliated with the Know Nothing Party, again ran into the Democratic machine, which supported longtime Democratic activist David Scannell in the September 5, 1855 election. It didn't hurt that Scannell was also a deputy sheriff under Sheriff Gorham.

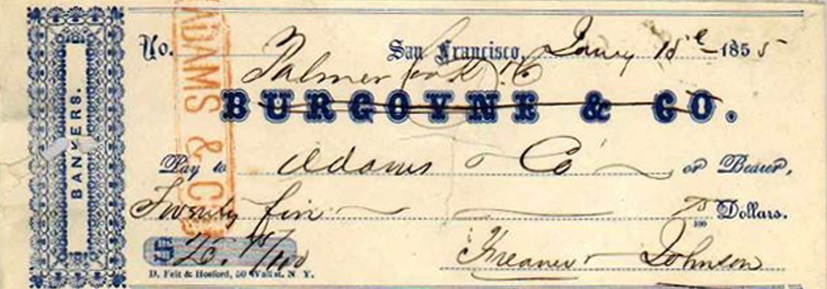

A $25.00 check signed by then former Sheriff Thomas Johnson and John Freaner in 1855 on a Burgoyne & Company check, a bank at 165 Montgomery Street. It was paid to Adams & Company with a correction that it was actually from an account with Palmer & Cook Company. Adams & Company at 99 Montgomery was a local delivery and shipping concern that expanded into banking and then failed in Panic of 1855. It was taken over by Palmer & Company, which explains the various notations on the check.

Johnson got a rather tepid mention that his "administration was so successful that it is a strong argument in favor of his election". But also, "He [Johnson] will doubtless receive the most of the Know-Nothing vote, besides the vote of all those who envariably vote for Southern men whenever such are in nomination-- and that is always-- regardless of party ties".

When the results came in, Scannell got 5,524 votes to Johnson’s 4,614; Whig candidate Alfred J. Ellis received 695 votes.

Sometime not long after the 1855 election, Johnson moved his family back to Kentucky, where two more children were born in their Georgetown, Kentucky home. Whether Johnson fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War is unknown. Thomas Johnson is buried in the Georgetown Cemetery, although the exact year of his death is also unknown.

References/sources:

Alta California from the UC Riverside CA Digital Newspaper Collection and the SF Public Library History Center; SF Public Library: SF City Directories Online; Christopher Nelson; Carl Koehler; SFSD History Online.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Notes on Early San Francisco Political Parties

1850 - Democrats, Whigs.

1854 – 1860’s (Civil War era)

The Democrats were split into nine sub-parties, divided mostly on the issue of slavery versus free soil.

1854 - Anti-slavery: Northern Democratic Party.

1854 - Southern Democratic Party (Chivalry)

Pro-slavery.

1855 - American Party (The Know Nothings)

Mostly former Whigs. Elected Neely Johnson Governor of California in September 1855.

1856 - Whigs disappear from the polical scene.

1856 - Republican Party emerges 3-18-1856

Anti-slavery and pro Black suffrage.

1859 - Lecompton Democratic Party.

1859 - Anti-Lecompton Democratic Party

“Lecompton” refers to a version of the Kansas State Constitution which supported slavery and which was signed in Lecompton, Kansas.

1860-1862 - Breckinridge Democratic Party.

1860 - Douglas Democratic Party.

1861-1862 - Union Democratic Party.

1861-1865 - The Copperheads or Peace Democrats

Anti-Civil War. This group opposed the Civil War and favored a settlement with the Confederates.

1856-1866 - The Peoples’ Party

A San Francisco party, an outgrowth of the Committee of Vigilance of 1856.

1877-1881 - The Workingman’s Party

A largely anti-Chinese, anti-immigrant, movement.