High Hopes for a New Era of Jail Rehabilitation

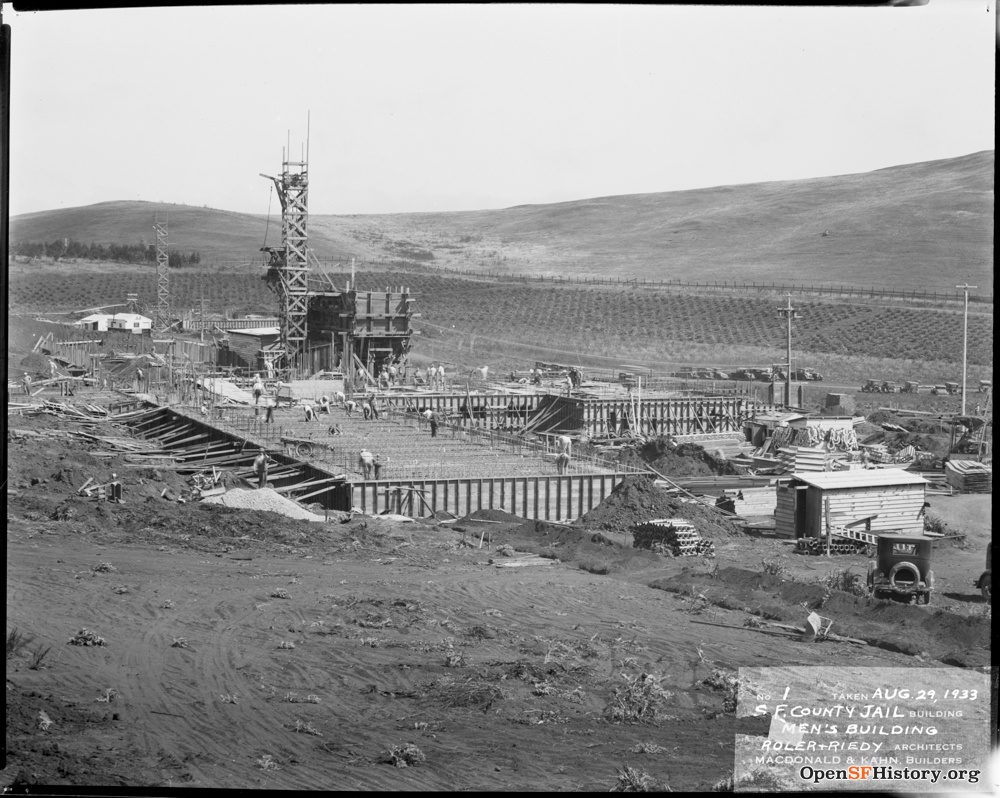

June 1933 saw the start of actual construction on San Francisco’s new county jail in San Mateo County, officially designted as County Jail No. 2. The political dust-ups over the new facility’s location were now replaced by the literal dust of mass construction.

County Jail No. 2 under construction in 1933. The facility and grounds were not inside San Bruno's city limits, but west of the city in rural northern San Mateo County. Despite that, throughout its long history the jail would be known as San Bruno, or simply "Bruno".

The electrical and plumbing work went to Alta Electric for $135,404 and $57,690 respectively. Director Worden made sure the local newspapers added that all the construction awards went to the lowest bidders.

Architects Albert F. Roller and Dodge A. Reidy had been picked on May 6, 1932 by Worden to design the buildings on the jail’s 242 acre rural compound. Roller and Reidy were given three months to come up with plans for a modern jail that would break the mold of the intimidating, dreary edifices that dominated the era’s jail and prison design.

The final costs for securing the land and building the actual jail facility as well as additional building construction would be just under $850,000.

“SF New County Jail: Rated the Finest in North America, Perhaps the World”

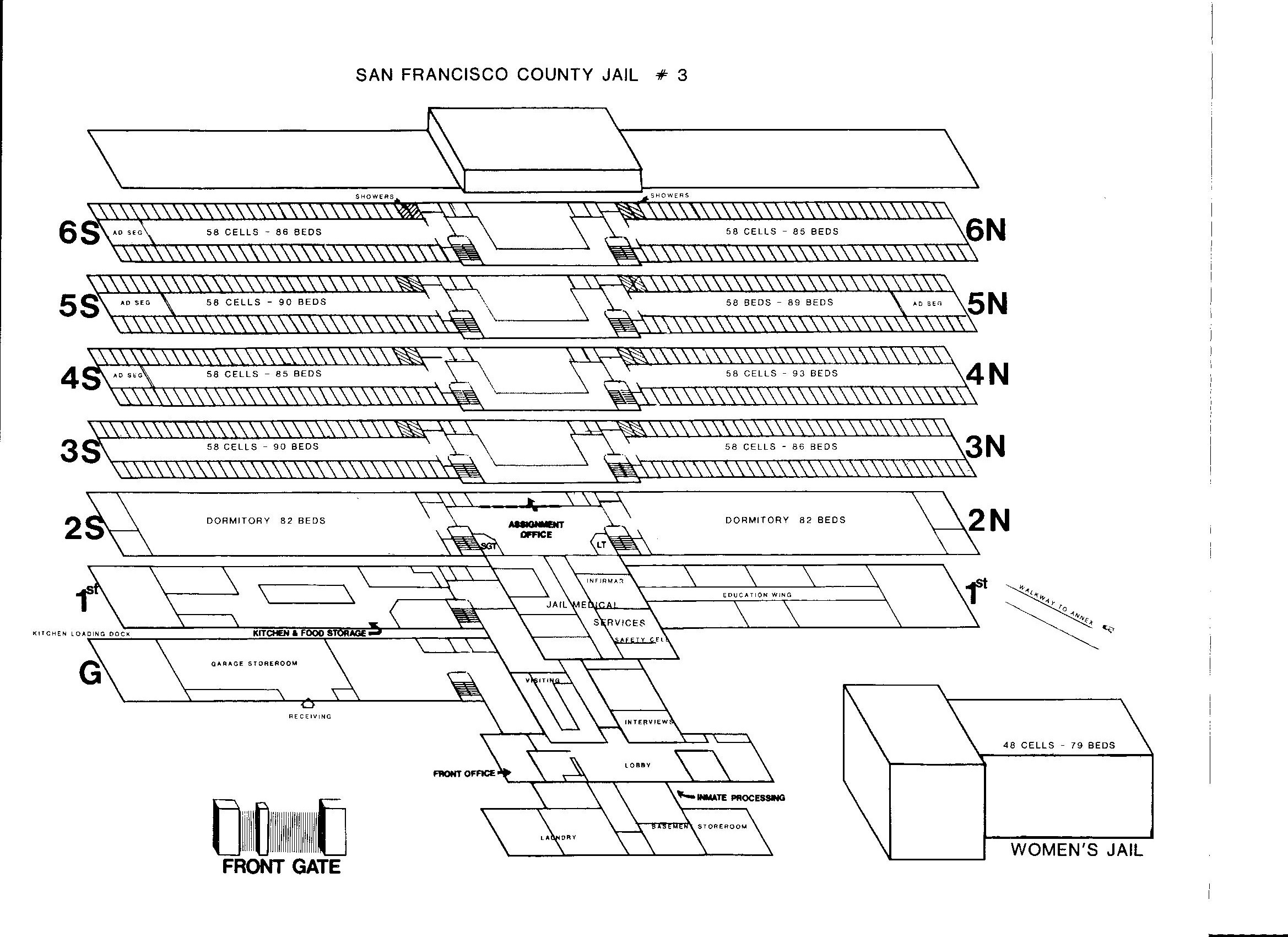

The jail would consist of a seven-story 600-cell men’s building designed in a modified “t” shape, with administrative offices, a kitchen, and a laundry area. The jail cells were separated into two tiered wings at mid-building by an administrative tower consisting of elevators, stairways, and deputy offices set in a five story rotunda.

Six hundred feet from the main jail, a separate L-shaped two-story “cottage” would hold 52 female custodies. In addition, several farm buildings were located about a quarter mile southeast of the jails to facilitate growing crops on the compound’s vast tracts of tillable land.

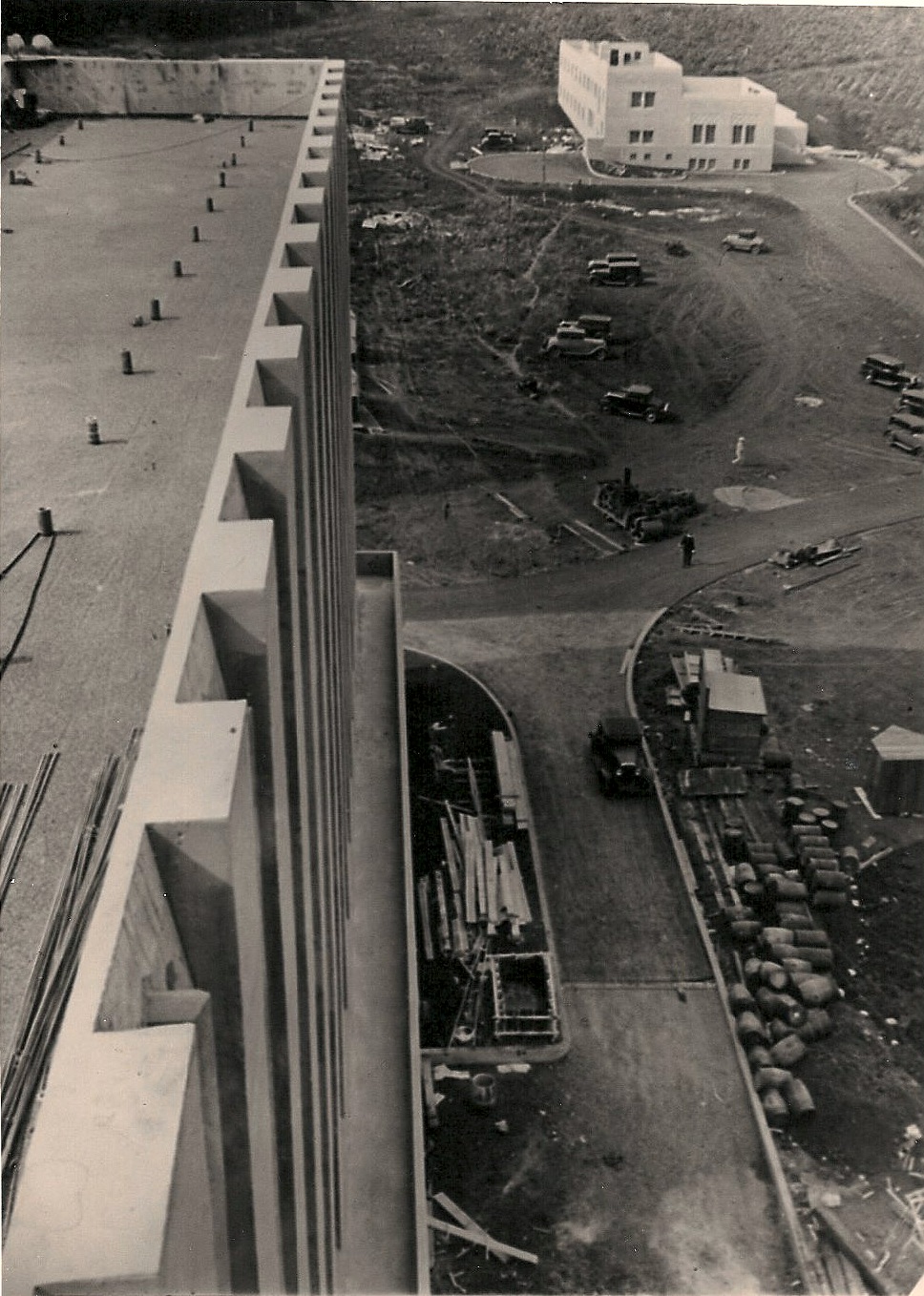

A view of the construction of the County Jail No. 2 women's jail as seen from the roof of the main jail building. The much smaller women's facility had its own kitchen, recreation area, medical office and deputy stations.

And of course all the compound’s buildings would be carefully fire-proofed with the use of large amounts of asbestos in the walls, floors and ceilings.

In the effort to be “modern” a number of design features were incorporated into the building that would cause serious security problems throughout the jail’s entire history.

Two of those design decisions in particular would undermine the jail’s fundamental safety and security.

First, the housing areas were located in long corridors that radiated from opposite sides of the central rotunda. The second floor had two open dorm-type areas on either side for inmate workers, but the cells on the third through sixth floors faced each other down the entire length of the wide tier.

As a result, when inmates were inside their cells a deputy at the tier entrance could not see into any of the cells or have clear visuals of the prisoners.

At the time this design choice seemed a logical and sleek way to house hundreds of county jail prisoners in one building. But that choice created a permanent high maintenance security challenge for supervisors and deputies, especially during evening and night watches when fewer staff were assigned.

Prisoners were essentially free to fight, commit sexual assaults, or make escape preparations unless a deputy happened to be standing directly in front of their cells.

The second critical security issue was the potential for inmates to have direct accessibility to the exterior of the jail facility.

Concrete forms being laid out to create the massive first floor of the men's jail, on August 29, 1933. In the left center background work can been seen being done on the women's jail. (From OpenSFHistory / wnp100.00393.jpg.)

At the new San Bruno jail it didn’t take long for determined prisoners to figure out they had direct outside access if they could find a way to cut through the window bars.

By the 1930’s the interior designs of state and local detention facilities had already begun setting prisoner cells in the interior of jail and prison buildings, with at least one safety corridor between the cell blocks and a building’s exterior.

But from the start, the City was determined that the new San Francisco County Jail would be cutting edge, with sunlight, fresh air and prisoner visual access being an integral part of modern prisoner rehabilitation.

Certainly during the design phase, the construction project, and at the opening of the new county jail at San Bruno there were good feelings and high hopes about the impact the building would have on the future of incarceration in San Francisco.

The ultimate goal was clear: to impact crime and the increasing numbers of alcohol and drug abusers who populated the City's South of Market and Tenderloin neighborhoods.

No one knows who coined the term “the sunshine jail farm”, but that quickly became the jail’s popular sobriquet as soon as it opened. The colorful nickname was freely used by City officials because it reflected exactly what those officials hoped the new jail would achieve.

Three Eras Defined the San Francisco's Jail in San Bruno

The operational history of the San Francisco’s first county jail in San Mateo County can be divided into three specific eras.

The initial optimism that surrounded the modern sunshine jail farm would be amazingly short-lived. By 1935 clashes with San Mateo County officials over questionable jail conditions and problems with escapees initiated a seventy year on-again-off-again war of words and legal maneuverings between the two counties.

At a time when simply being drunk in public was a crime that often incurred a month or more of jail time, the original idea behind the San Bruno jail was to get alcohol and drug abusers out of the City and into the “healthy” environs of the jail farm to do their time.

It was a tidy but misguided formula: the City’s street drunks dried out on the farm and the vegetables they planted and grew would be turned into prisoner meals by the jail kitchen. There was little consideration of the impact of future changes in State law or impending shifts in the City’s population that could compromise the new jail’s narrow housing profile.

The second era of San Francisco’s county jail at Bruno was the 1940s through the 1960s, when prisoner demographics and laws began to dramatically change.

The hapless “Skid Road drunks” who in retrospect needed medical assistance and therapy more than jail time, were now replaced by more serious offenders. This is also when racial disparity in arrests and incarceration began populating county jails and state prisons around the country with disproportionate numbers of Black and Latino males.

The third and final chapter in the jail’s saga started with severe inmate overcrowding in the 1970s and the rapidly deteriorating physical plant of a forty year old building with serious staff and prisoner safety issues.

The efforts to keep deputized staff and prisoners safe, to maintain the building’s crumbling infrastructure, and at the same time to fight the political battles required to replace the facility would be a thirty-five year struggle.

Telescoped design scheme for San Francisco County Jail No. 2 San Bruno. The administrative offices, deputy lockerroom, communications center, and prisoner visiting rooms were in the front section of the building.

Each of the prisoner housing floors was designated by their floor number and either the north or south wing.The first prisoner housing floor was "2 South" and "2 North", both open dormitories. The main deputy office was called "The Assignment Office", located directly between the two prisoner dorms on the 2nd floor.

Floors 3 through 6 had traditional jail cells with a central rotunda dividing the north and south wings of cells. The five story rotunda gallery picked up voices and other noises and echoed them throughout the facility. The jail kitchen and food storage was located on south wing of the 1st floor; the 1st floor northwing contained a series of classrooms and storage areas.

The location of the woman's jail was actually 600 feet to the northeast of the main jail and the front entry security gate was located some 800 feet away on the main road access to the compound.

The Sunshine Jail Farm Gains “World-Wide” Fame

The nature of the history of San Francisco’s jails is that it is rare to go back more than thirty years and find the kind of specific documentation and contemporary analysis that fully illuminates that history.

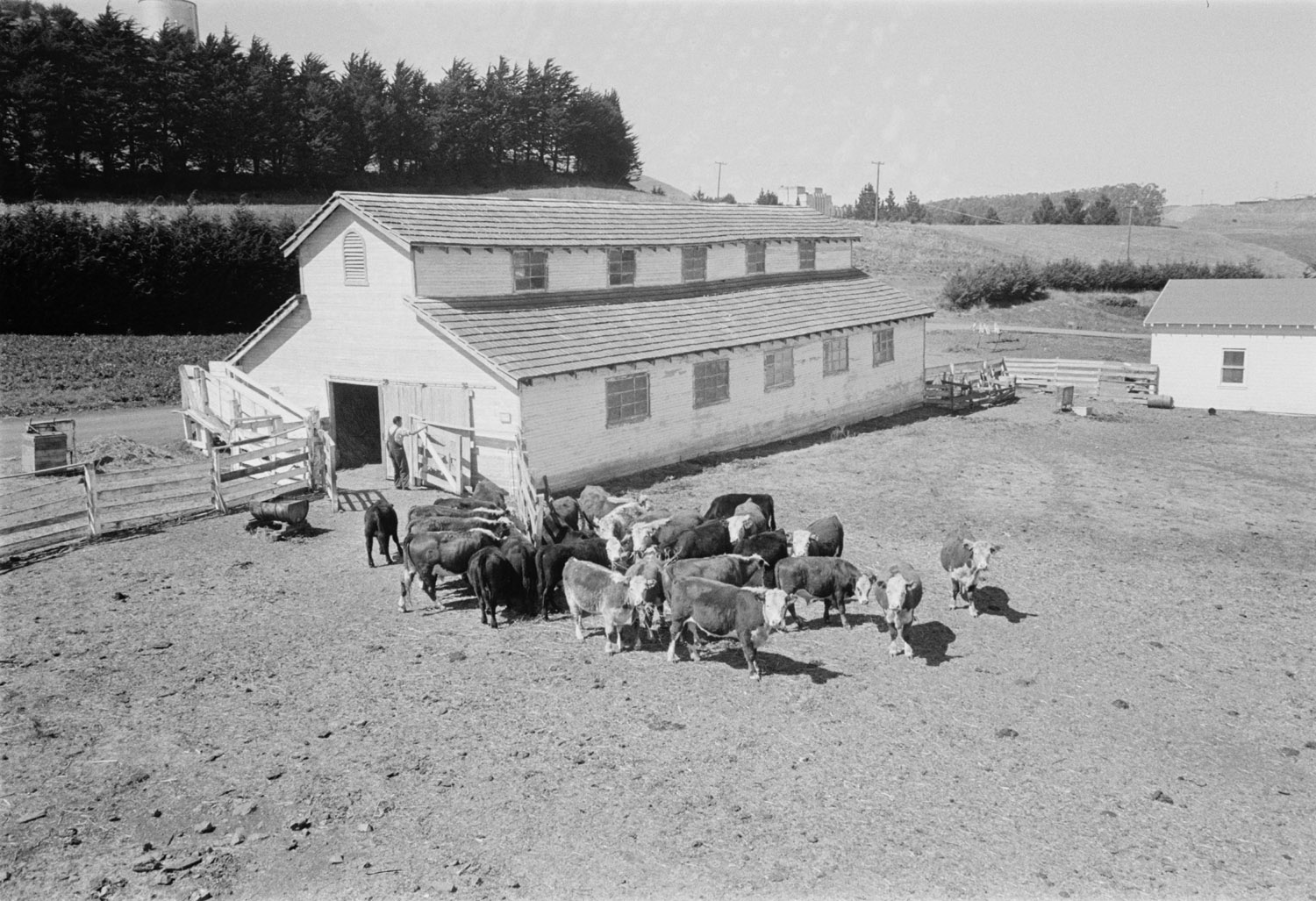

The jail's barn, livestock pens, and acres of rich farm land were a stark contrast to the main jail building. All were tucked into the rolling coastal hills with the Pacific Ocean only two miles due west.

The SF Chronicle piece was headlined "New S.F. Jail To Be Put Into Use After July 1", and subtitled "Unique Penal Institution Will Be Rated as Best in All Nation". Sheriff William Fitzgerald's quotes in the piece perfectly articulated the City's expectations that the rural atmosphere of the new facility would change everything.

Fitzgerald said the land will be farmed by the prisoners and he expected their work would not only help feed the hundred of inmates at the jail, it would support a working farm with "hogs, rabbits and chickens to reduce jail operating expenses." He also noted that there would be a sauerkraut factory on site to ulitize the cabbage grown on the farm.

"We can work practically every man outside for the greater part of the year", Fitzgerald insisted. "That will conserve the prisoners' health and keep up their morale, and assist in reclaiming many of the young men for society."

The Chronicle article also noted that "At first glance the buildings look more like a college group or hospital, but make no mistake, it is a real jail." And that "a successful effort has been made to make the place look cheerful. For instance, the hundreds of windows. There seems to be an absence of bars, but the bars and steel are there, disguised as cross supports for the sash and glass."

The County Jail No. 2 farm was intended to not only provide food for the jail's prisoners, the idea was to also supply other city institutions like the Laguna Honda nursing home and Juvenile Hall. Cows, pigs and rabbits were raised at the farm and a variety of crops.

In the 1920s and 1930s a yearly booklet called the “San Francisco Municipal Record” was published. Funded by enormous amounts of advertising, it was actually privately published “for the City and County of San Francisco” by the local business community.

The basic purpose of the “Record” was to provide PR for elected officials under the guise of a publishing a city government directory.

It certainly looked official and featured profiles and statements from every City and County department head or their representatives. The “Municipal Record” invariably extolled City projects and achievements, praised elected officials, and highlighted the enormous amount of great work being done on behalf of the citizens of San Francisco.

The August 1934 issue, as it turned out, featured a number of in depth articles about the City’s new jail in San Bruno and the people behind it. While much of the publication is pure political puffery, it also includes the kinds of details that often get lost in the fog of history.

The issue’s lengthy and praise-filled lead editorial is humbly titled “Honor to Sheriff Fitzgerald” and it would seem to permanently enshrine the man who fought so hard to replace the aging Ingleside Jail with the new “sunshine” jail and who personally chose its location.

But such are the politics of politics: Sheriff William Fitzgerald, three years into his second term and basking in the glow of creating “the most modern jail in the world”, would be voted out of office in 1935.

More on that later.

On July 9, 1934 Sheriff William Fitzgerald presents the ceremonial key to the old Ingleside County Jail to San Francisco Mayor Angelo Rossi at the dedication of the new County Jail No. 2 San Bruno. The Ingleside jail grounds would be turned over to the City's Park and Recreation Department. Also in attendance were Mrs. H.G. Douglas and Adelbent Schapp of the West of Twin Peaks Booster club. Several neighborhood organizations led the effort to close the Ingleside facility.

In actuality, several Italian governmental officials toured the new jail. No doubt they were in San Francisco at the behest of Mayor Angelo Rossi, whose support of Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini would eventually help end his own political career as San Francisco’s mayor after three terms.

But at the time San Francisco’s new county jail was an occasion of hope in solving the City’s social ills and pride in being on the cutting edge of international incarceration reform.

The New Jail Opens for Business

On June 30, 1934 the San Francisco Chronicle announced the public was invited to attend the dedication of the new jail the next day. And on July 1st Mayor Angelo Rossi formally accepted the San Francisco County Jail and ceremoniously turned the facility over to Sheriff William Fitzgerald.

Over a photo of the stunning new building in the July 1, 1934 SF Chronicle was the headline “It Looks Like A Resort Hotel”.

Crowds of curious citizens from both San Francisco and San Mateo County accepted Sheriff Fitzgerald's invitation to tour the new men's and women's facilities and the jail's various farm buildings. Marveling at the pristine cement floors and impeccable cells, visitors also saw the jail’s vast kitchen, laundry, and boiler room areas, as well as its sauerkraut factory-- built to render the cabbage that would be grown at the jail’s farm.

Sheriff William Fitzgerald's personal secretary, C. I. Haley, operates the controls levers of the new jail's advanced electronic cell door system on May 21, 1934.

Two city workers, officially designated as 052 Farmers, were hired by the City to oversee the jail’s agricultural and animal projects. Their official salary was $210 each a month, minus $10 a month for living accommodations on the grounds.

The jail’s water needs came from a massive 273,000 gallon steel water tank built on a hill just south of the main jail. It was fed by a 3.5 mile, ten inch high pressure cast iron pipe from Lake Pilicitos (now Pilarcitos Lake), located in the hills several miles west of Upper Crystal Springs Reservoir.

On September 14, 1934 a fleet of buses transferred all the male prisoners from the old Ingleside Jail some 12 miles to the new jail, now officially designated as “San Francisco County Jail No. 2”. State police in a dozen vehicles joined SF Sheriff deputies in safely escorting some 400 prisoners down San Jose Avenue to Skyline Boulevard and the new jail.

Female inmates from the Ingleside Jail soon followed and Sheriff Fitzgerald formally turned over the crumbling, 63 year old Ingleside facility to the City’s Department of Parks and Recreation.

The final prisoner transfers occurred on December 4, 1934, when ten female prisoners were transported from the Kearney Street Hall of Justice jail to San Bruno.

Almost as an omen of things to come, it did not take long for County Jail No. 2 to have its first prisoner escape.

On February 25, 1935, just five months after the jail opened, twenty-two year-old Randolph B. Waite made San Francisco Sheriff’s Department history when he bolted over the jail’s perimeter fence and scurried up the coastal hills toward Pacifica. He had been working on the jail grounds as an inmate worker.

Mr. Waite sported a lengthy record of petty crimes and had been sentenced to a year in the county jail for burglarizing the home of one Fred Grimer at 250 Franklin Street in San Francisco. There is no record of Waite being recaptured.

On March 31 Edward Gleason, serving three years for burglary, became the jail’s second successful escapee. He was recaptured by San Mateo law enforcement and put on trial for felony escape.

Gleason’s case would become the first of many battles over the jail between the two counties.

Sheriff Fitzgerald Trips Over His Political Baggage

It turns out the public relations high that Sheriff William Fitzgerald enjoyed when San Francisco County Jail No. 2 opened was just a respite in his otherwise tumultuous second term of office.

A native San Franciscan, in 1907 William Fitzgerald earned a degree in engineering at St. Mary's College in Oakland, then located at 30th and Broadway. In 1928 St. Mary's moved to Moraga, CA after a fire damaged the Oakland campus. Fitzgerald became San Francisco's Assistant City Engineer in 1912. He was was soon noticed by Mayor James (Sunny Jim) Rolph who mentored Fitzgerald, added him to his re-election team, and kick-started his political career.

Spaulding had at one time also been Fitzgerald’s Undersheriff. Particularly nasty were Spaulding’s election accusations that Fitzgerald was receiving personal payoffs from potential construction firm bidders and from San Mateo County land owners all eager to cash in on the building of a new jail. While those charges were never proven, it dented Fitzgerald's carefully honed image as the academic public servant who was above reproach.

According to an article in the November 4, 1931 San Francisco Chronicle, right after he won the election William Fitzgerald “left for a rest of ten days in Long Beach on the advice of his physician.”

Fitzgerald had also been slammed during the campaign for issuing some 210 gun permits to San Francisco citizens which appeared to be payoffs to his supporters.

He had additionally appointed hundreds of “special” or “courtesy” deputies who did not actually work for the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department. They were either Fitzgerald campaign supporters and contributors, or potential future contributors he wanted to impress.

These “courtesy deputies” were sworn in by Fitzgerald, given an official badge (different than actual SF deputy sheriff stars), and allowed to possess and carry firearms. Unspoken was that these “special” deputies could also use their status to receive a variety of special privileges.

Three examples of the badges Sheriff William Fitzgerald handed out to thousands of his supporters and political friends. They were appointed as "courtesy deputies" and inherent in that semi-official status were special privledges such as posession of firearms and presumably whatever else the holder could get away with. (From the collection of Undersheriff Carl Koehler.)

In January 1932 the names, occupations, and addresses of some 2,000 courtesy deputies were filed by Fitzgerald with the County Clerk for public inspection.

Not helping matters was the arrest and January 1932 trial of Andrew Mareck, one of Fitzgerald’s courtesy deputies. Mareck and an accomplice were charged with the murder of Laguna Honda nurse Anita Lund, whose battered body was found on Rockaway Beach.

At a time when abortion was illegal, Mareck was running an underground abortion mill with a petty criminal named Mario Muratore. The suspicion was that Lund’s procedure had gone wrong and she was beaten to death and her body dumped to cover the crime up.

Mareck’s Sheriff’s Department “courtesy ID card” had been routinely renewed for 1932 just days after he was charged with Lund’s murder. When Fitzgerald found out, he immediately rescinded Mareck’s courtesy deputy status but the damage had been done.

What Was Up With “Doc”

This is where the saga of Andrew Mareck goes from somewhat interesting to criminally epic.

Andrew Mareck and his wife Thelma. "Dr." Mareck was one of Sheriff Fitzgerald's "courtesy deputies". He was arrested with his wife in the robbery of a Santa Rosa speakeasy and the shooting death of a police officer. Mareck was also suspected in the murder of one Joseph Sole who was about to testify in federal court against counterfeiter Eddie Quinones, a member of Mareck's gang. This is from a February 28, 1933 SF Chronicle photo montage.

The San Francisco DA retried Mareck in March but he was acquitted by that jury on March 23rd.

Almost year later, on February 26, 1933, Santa Rosa special police officer Carlos Carrick was shot to death during a gun battle in an alley next to a local speakeasy. Mareck and several others were identified by witnesses and arrested for robbing the speakeasy and killing officer Carrick.

Mareck insisted he was drunk the night of the crimes and had no idea that his companions were up to no good. But slowly the police pieced together the fact that Andrew Mareck was actually the leader of a multi-tasking gang of Bay Area criminals who robbed banks, dabbled in counterfeiting, and performed the occasional abortion.

Mareck’s #1 gunman, F. B. (“Slim”) Hoyt, was the triggerman in officer Carrick’s killing and was also still at large. Although wounded in the arm during the fierce gunbattle with officer Carrick, Hoyt dutifully sent a letter to a local Santa Rosa newspaper asserting that Andrew Mareck and the other gang members were innocent of Carrick’s murder because he had committed it.

As the trial continued and defense expenses mounted, Slim Hoyt and the remaining at-large gang members began robbing local banks to raise trial money for their boss Mareck and his remaining two co-defendants.

On May 9, 1933 Hoyt and the gang robbed the Bank of Pinole of $15,000. The next day they hit the American Trust Bank on East 14th Street in Oakland taking $1,000.

Hoyt was eventually arrested and he and Mareck and several others were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Mareck ended up being paroled twice, each time ending up back in prison after it was discovered he started running abortion mills again-- first in Menlo Park and later in Marysville.

A particularly interesting part of this story is the evolution of Mareck’s identity in newspaper stories throughout his criminal life.

When Mareck was first arrested for the Lund abortion murder and IDed as one of Sheriff Fitzgerald’s “courtesy deputies”, he was described in the newspapers as “Andrew Mareck”. During those trials he was then referred to as “Dr. Andrew Mareck”, which morphed into “Dr.” Andrew Mareck as the abortion part of the story was revealed.

When he was prosecuted in the Santa Rosa speakeasy murder trial he was referred to as “Doc Mareck”, leader of the Doc Mareck gang.

In 1957 Mareck’s wife was convicted of a felony and he divorced her from his cell in Folsom Prison. By then the SF Chronicle referred to him as “Andrew (Old Doc) Mareck”.

But Back to Our Story

Thanks to his perceived lapses in ethics, opponents saw Sheriff William Fitzgerald as politically vulnerable just as he prepared to campaign for a third term.

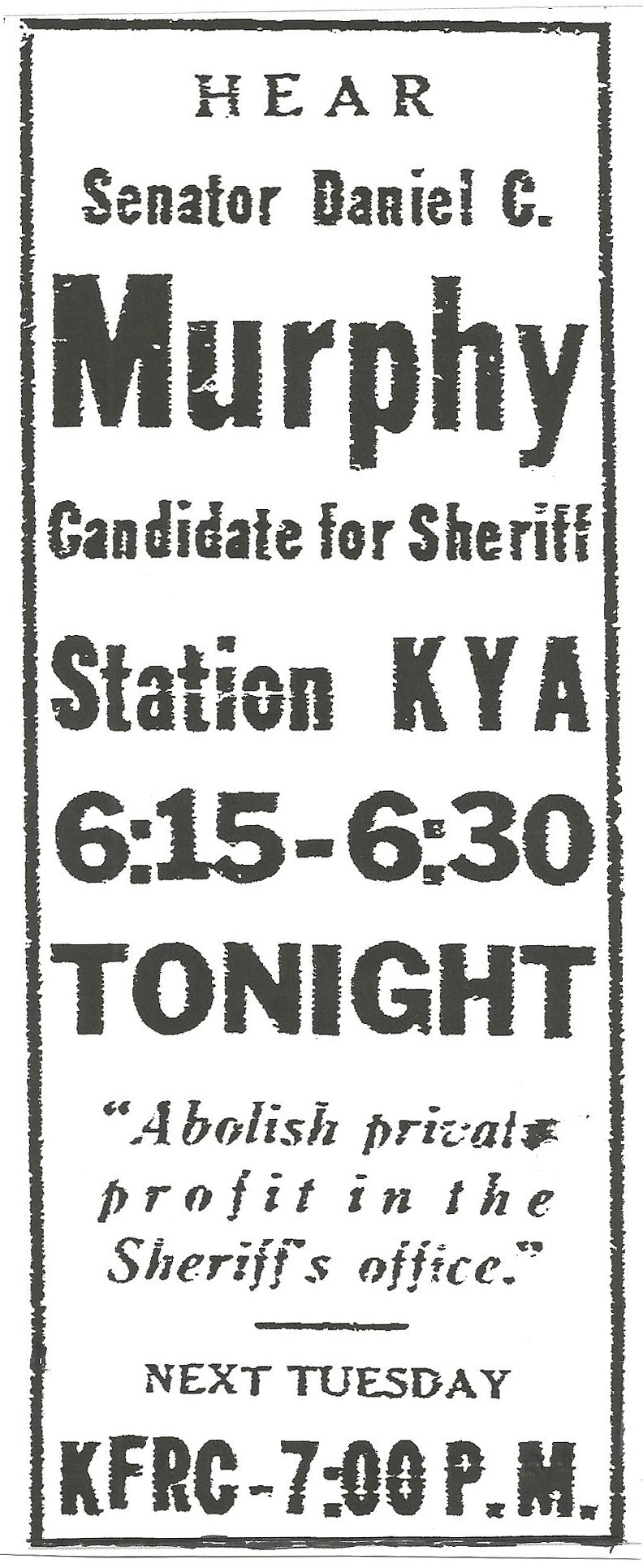

By the early 1930s even local political candidates used the medium of radio to reach more voters. In the 1935 campaign for San Francisco Sheriff, candidates Daniel Murphy and William Fitzgerald both appeared on radio stations KYA and KFRC to plead their cases.

Daniel Murphy had solid and longstanding ties with the labor movement and he cast Fitzgerald as using the office of Sheriff to profit himself and his family. Quickly the City’s voters came to believe that Fitzgerald, as they say, didn’t pass the smell test.

After being elected to his first term in 1927, Sheriff Fitzgerald had appointed his brother to run the county jail commissary as a for-profit, private enterprise. Also, throughout his two terms of office Fitzgerald ended up handing out some 5,000 “courtesy deputy” badges to his supporters and contributors, which allowed them to carry firearms and apparently enjoy other privileges.

On another front, several members of the Board of Supervisors went after Fitzgerald for awarding those 210 firearms permits to various San Francisco citizens. When he was accused of flooding the City with guns, Fitzgerald sounded very Nixonesque, claiming the issue was brought up to “give aid and comfort” to his political enemies.

Appearing on radio station KYA on October 8, 1935, candidate Dan Murphy’s campaign theme was “Abolish private profit in the Sheriff’s office”. He was endorsed by the Progressive Party on October 20th and by the San Francisco Chronicle on October 31st.

Another controversy that would dog Fitzgerald even after he lost the 1935 election involved charges that he padded the Sheriff’s Department’s state prison and mental patient transportation expenses.

It seems odd now, but Fitzgerald’s salary as Sheriff was $8,000 a year plus a series of per diem payments paid directly to the Sheriff when his deputies transported prisoners to a state prison or to a state mental institution. Vouchers would be filled out and submitted for payment by the State with little oversight.

In May 1936, barely five months after being voted out of office, Fitzgerald faced possible criminal prosecution for some $4,000 to $5,000 in false vouchers submitted ($70,000 to $88,000 today). It was discovered that when deputies made one trip, receipts for two or three trips were actually submitted for reimbursement.

On May 29th Fitzgerald told the San Francisco Chronicle “I do not see where I have been fraudulent”, adding “any suggestion that I benefitted personally from the irregularities in unfounded and unfair.”

Although Fitzgerald publicly blamed his civil service “underlings” for the discrepancies he also stated that would be willing to pay the money back.

In what may have been one of the first organized public statements from civil service San Francisco deputies, a group of them issued a press release saying that, under Fitzgerald, transportation deputies were directed to simply sign and submit blank transportation vouchers and that sometime later the dollar amounts were filled in.

Ultimately no criminal charges were filed in the matter and the issue seemed to disappear, suggesting that perhaps a political solution was reached between the State and the City.

The election of November 5, 1935 featured a record-setting turnout of 185,568 voters, 20,000 more than in any previous municipal election in the City’s history. Daniel Murphy’s labor connections came through to the tune of 98,426 votes to Fitzgerald’s 59,541.

Minor candidates Ben Legere (11,126 votes) and Ray Conley (4,304 votes) rounded out the Sheriff’s race. Ben Legere was an acclaimed stage actor, union official, and San Francisco labor activist who died in 1972 at the age of 85.

Ray Conley was a machinist who also unsuccessfully ran for Sheriff in the November 1939 and November 1943 elections. The 1939 City election was also notable for the District Attorney’s race in which Edmund G. “Pat” Brown lost to incumbent DA Matthew Brady.

Four years later Pat Brown would beat Brady for DA and begin a legendary political career that would lead to the Governor's mansion in Sacramento.

As for William Fitzgerald, his career after two terms as San Francisco Sheriff was not particularly successful.

October 1936 found him filing a complaint with the City when he took the civil service exam for county clerk and only finished 5th among 8 candidates. Then in March 1939 he tried unsuccessfully to get the $6,000 a year post as California’s Chief of Narcotic Law Enforcement.

Realizing that challenging Sheriff Dan Murphy’s November 1939 reelection bid would be a lost cause, Fitzgerald instead ran for the SF Board of Supervisors. He finished 14th out of 23 candidates with 55,254 votes and never ran for public office again.

Amazingly, William Fitzgerald lived until 1965, dying on March 3rd at the age of 81. Had he lived another fourteen years and nine months he would have been alive for the election of Michael Hennessey, the Sheriff who would eventually tear down the San Bruno jail.

San Mateo County Strikes Back

Although San Mateo County officials had grudgingly agreed to allow San Francisco to build its massive county jail in a rural corner of their county, the after-politics of the deal quickly became negative and complex.

County Jail No. 2 jail escapes and poor SF deputy staffing prompted the San Mateo County Grand Jury to request reimbursement for the cost of tracking down and prosecuting escaped San Francisco prisoners. On November 24, 1935, the San Mateo Grand Jury asked the San Francisco Grand Jury to help them investigate conditions at the new jail. The SF Grand Jury did not accept their invitation and relations between the two counties began to get frosty.

Several weeks later San Mateo County Clerk E.B. Hinman sent San Francisco a bill for the recapture and felony trial of recent San Bruno escapee Edward Gleason— a total of $239.75. SF City Controller Leonard Leavy denied the request through his attorney.

Complicating San Mateo County’s attempts to compel San Francisco to properly staff and manage its county jail in San Bruno were the ongoing discussions and detailed planning to merge the two counties.

As detailed in “Part 1” of this series, there were political and business interests in both counties that saw great advantages for San Francisco to extend its county line south down the Peninsula and its original 1850 boundary along San Francisquito Creek in Palo Alto.

Getting into a political pissing match over County Jail No. 2 would only create the kind of bad will and legal complications that could scuttle any chance to reunify the two counties.

Not helping to keep the political temperature down was San Mateo County Sheriff James McGrath’s request that the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors approve the purchase of a Thompson submachine gun for his department. He wanted the weapon to be staged in the north county for added protection when County Jail No. 2 jail breaks occurred.

If San Mateo elected officials were trying to tread lightly around San Francisco’s problems with its new county jail, others were not.

Jail Overcrowding and the First of Many Bad Report Cards

On May 24, 1942 the Mental Hygiene Society of Northern California slammed both of San Francisco’s county jails in a report whose findings were splashed across the front page of the Chronicle: “Prison Probe: City’s Jails Destroy Men Mentally, Experts Charge”.

On June 30, 1942 145 minor offender prisoners at County Jail No. 2 were allowed to sign up for a year's probation to work as part of the national war effort. This was the first of several groups released on probabtion from the San Bruno jail to help replace workers serving in the military in Europe and the Pacific.

Municipal Court Judge George Harris held court sessions in the second floor rotunda of the jail; those registering were bussed to Oakland and put on a train to report to their work assignments. Most performed maintenance duties on the Western Pacific Railroad's line between Oakland and Salt Lake City.

If they worked for the entire year the prisoners had their sentences revoked and they received the prevailing wage for their work.

As to the Society’s charge that alcoholics sent out to County Jail No. 2 routinely died there, Sheriff Dan Murphy responded with an unfortunate quote: “That is not true”, he firmly declared. “They did not die at the jail. They were sent to the county hospital.”

World War II brought jail overcrowding relief thanks to Municipal Court Judge George Harris. Judge Harris arranged to have several groups totaling almost 400 San Bruno county jail prisoners released on a year’s probation to work at prearranged war industry jobs in shipyards, farms, and railroad construction gangs.

Harris was an advocate of treatment over jail for drug abusers and proudly noted that only two or three the newly paroled inmates had “gone south” under his plan.

News from County Jail No. 2 for the rest of the 1940s, and for decades beyond, became an endless recitation of newspaper stories about escapes, deaths in custody, deteriorating conditions, and failing institutional report cards.

None of which stopped other counties from requesting temporary San Francisco jail space for their own crowded county jails. In the early 1940s Marin County became the first outside county to request the use of jail beds at County Jail No. 2, while the Marin County Jail was being repaired.

In January 1947 San Mateo Sheriff James McGrath sent a written request to Sheriff Daniel Murphy for the use of County Jail No.2 jail beds to ease the overcrowded conditions in his county’s only jail in Redwood City. It was noted that at the time San Francisco’s San Bruno jail had 425 male prisoners and a capacity of 600.

On April 22, 1948 twelve San Mateo County prisoners were moved to the San Bruno jail for an undetermined time. In a strange move, it was felt that to meet some obscure legal technicality Sheriff Dan Murphy needed to be officially designated “San Mateo County Sheriff in charge of San Mateo prisoners at Jail No. 2”.

As the SF Chronicle wrote it up, “San Mateo county got a second jail yesterday. The jail came complete with a second county Sheriff.”

During the next fifty-eight years San Francisco officials made attempts to improve conditions and reclaim the initial progressive goals of County Jail No. 2.

In May 1949, District Attorney Edmund G. Brown requested the Board of Supervisors provide $50,000 to fund a clinic for alcoholics at the San Bruno jail on a trial basis.

The clinic was successful and on August 22, 1949 the Board of Supervisors approved an additional $11,550 to permanently hire a psychiatrist (at $800 a month), a psychiatric social worker ($300-360 a month), and a clerk-stenographer ($200-$250 a month) to staff the project.

The Chronicle called the clinic “the first official attempt here to handle Skid Road alcoholics as sick people who respond to treatment rather than depraved, hopeless bums and criminals.” Treated alcohol abusers were tracked after they left the jail and the results were encouraging.

But by the early 1950s San Francisco’s county jail in San Bruno, less than 20 years old, was a disgraceful wreck. Deferred maintenance, inadequate budgets, substandard food, poor staffing and occasional corruption had turned the sunshine jail farm into a penology nightmare.

A Time of Change for the Sheriff’s Department

In December of 1951 Sheriff Dan Murphy suffered a severe heart attack followed by medical complications in January. On March 18, 1952 Murphy died at the age of 70, just over two months into his fifth term as San Francisco Sheriff.

San Francisco Mayor Elmer Robinson immediately appointed Coroner John Kingston as Acting Sheriff. Days later Mayor Robinson announced that he had picked Board of Supervisors member and lifelong Democrat Daniel Gallagher to officially finish Murphy’s term, and swore Gallagher in on March 23, 1952.

January 8, 1946 San Francisco City Hall: Board of Supervisors President Dan Gallagher congratulates newly elected superviors P. J. Murray, Marvin Lewis, and George Christopher. In 1956 Christopher would be elected as the last of five consecutive Republican San Francisco mayors, serving two terms until 1964.

After serving in the State legislature, Supervisor Dan Gallagher seemed to be on track for a stellar political career but his appointment as sheriff after the death of Daniel Murphy was a curious career choice.

It didn’t take long for Sheriff Gallagher to become directly involved in operational issues at the San Bruno jail.

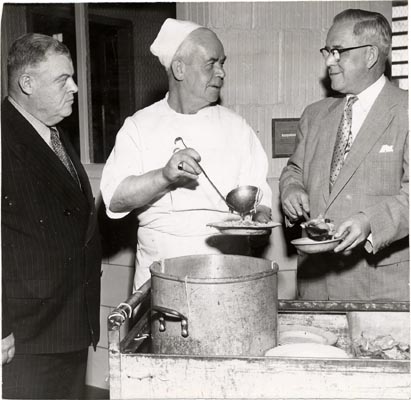

On May 5, 1952 there was what was called a “riotous demonstration” as four tiers of prisoners first refused breakfast (“dry mush, black coffee, stale bread”) and then lunch (“bean soup, salt meat, and coffee”).

Shouting and banging tin cups on their jail bars Hollywood-style, the inmates lit bundles of newspapers and books on fire in the tiers then flooded the sinks and toilets in their jail cells. A number of inmate workers were beaten and deputies fought with dozens of inmates as they struggled to regain control.

This was probably the largest classic riot in the jail’s history.

Sheriff’s Captain Charles Cunningham grabbed the jail’s only outside phone and called Sheriff Dan Gallagher directly for help. Gallagher immediately drove out to the jail and met with the prisoners, dutifully recording their grievances. Then he went directly from the jail to the Board of Supervisors chambers and requested they immediately approve four additional budgeted deputies for County Jail No. 2.

The final damages to the jail as a result of the riot came to $30,000 (almost $265,000 today). A number of deputies and inmates were injured, but none seriously. Predictably, San Mateo County officials jumped at another chance to protest the existence of San Francisco's massive, overcrowded jail in their backyard.

On May 22, 1952 Sheriff Dan Gallagher made page 1 headline news in the San Francisco Chronicle when he presented Mayor Robinson with a laundry list of what he termed the “deplorable conditions” in County Jail No. 1 at the Hall of Justice and at County Jail No. 2 in San Bruno. He clearly understood that the San Bruno jail had the potential to be a permanent open political sore, and one that needed immediate attention. Gallagher was proactive and used his political capital to work the Board of Supervisors and the Mayor; he also had no problem going to the local newspapers to help get things done.

Gallagher said the current state of the San Bruno jail was particularly terrible. His list included:

• Inadequate and stale inmate food; he called for the City Controller to conduct an audit of all prisoner food purchases made over the past year.

• Many cell and tier locks needed repairs at an estimated cost of $1,900 ($16,750 today).

• There was a shortage of guns and ammunition for outside jail deputies.

• Only one outside telephone line existed on the entire compound, leaving the jail vunerable to complete isolation.

• The jail’s internal communications system was broken and when the facility’s standby electrical system was tested it failed after two minutes.

• Equipment on the jail farm was inoperable and the Health Department recently had to be called in to clean out the rat-infested barns.

• Forty-five of the farm’s 50 hogs died of disease in March and the other five had to be killed.

• Laundry machines, jail vehicles and trucks, food refrigeration units, and the main boiler were in need of emergency repairs and there were insufficient stores of prisoner commissary items kept at the jail.

• Gallagher had fired a civil service jail storekeeper at San Bruno who was black market selling cigarettes to prisoners. When he later checked, Gallagher found that the man had been allowed to resign after “satisfactory service”.

One unescapable theme would run through the County Jail No. 2 story throughout its long history: the fact that the jail was 16 miles from City Hall and located in another county allowed repeated long periods of neglect and out-of-sight-out-of-mind mismanagement by the City of San Francisco.

And then, all of a sudden, everything changed.

Pierre Salinger Makes His Journalistic Bones Behind Jail Bars

From out of nowhere the front page of the January 26, 1953 San Francisco Chronicle screamed the following four headlines, the top two in bright red ink:

“Exclusive: Inside California’s Jails”

“COUNTY JAILS EXPOSED -- STORY OF CRUELTY, FILTH”

------------------------------------------

"Brutality... Crowded Cells"

"Chronicle Reporter Does Time: Shocking Account"

The story’s byline was by Chron crime reporter Pierre Salinger, who wrote six more installments in this series over the following two weeks. The expose would sell thousands of newspapers and cause political ripples that ultimately led California Governor Earl Warren to demand reforms in California prison and jail administration.

Native San Franciscan Pierre Salinger had an American Jewish father and a French Catholic mother. He was a child piano prodigy and on track to become a concert pianist.

In 1942 at the age of seventeen Salinger enlisted in the Navy and was a Lieutenant JG when he received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his actions of October 1945 at Okinawa.

Lt. Salinger volunteered to lead a rescue party to retrieve six sailors stranded on a reef after their vessel had been wrecked in a severe typhoon. With the eye of the typhoon passing over the reef Salinger and his crew plunged into the churning ocean with just mintues to spare before the rest of the storm hit. Everyone involved survived.

Salinger first worked the night beat and was assigned to cover the San Francisco Police Department and the criminal courts. His hard work and excellent writing soon got him bigger and more important stories to cover.

While covering a meeting of the American Friends Service Committee about local jail conditions he cornered meeting chairperson State Attorney General Edmund G. Brown Sr. with a proposition. Salinger wanted to covertly go underground, get arrested and write about county jail conditions from the inside posing as an inmate.

Attorney General Brown was intrigued and arranged to make it happen. One week later Salinger was arrested at two in the morning on a seedy Stockton, California street for being drunk in public and breaking into a car. He was booked and taken to the San Joaquin County Jail.

During his undercover research, done over much of 1952, Pierre Salinger’s identity was never discovered by the police who arrested him and the two sheriff’s departments in whose jails he spent time. Following his San Joaquin experience, Salinger was arrested in Bakersfield, CA (also for drunk in public) and did time in the Kern County Jail.

Both the San Joaquin and Kern county jails would be replaced as a direct result of Salinger’s expose and the powerful political fallout that followed.

After the Chronicle exposés were published, Salinger followed up with straight profiles of several other county jails, including County Jail No. 2 in San Bruno and the Alameda, and Santa Clara County Jails. Salinger rated the Santa Clara County Jail “Worst in the State” and Alameda’s new Santa Rita facility “Best in the Nation”.

He noted that in 1947 Alameda Sheriff H.P. Gleason got the US Navy’s barracks and over 1,000 acres of land comprising Camp Shoemaker near Pleasanton in Southern Alameda County for exactly one dollar.

It was renamed the Santa Rita Rehabilitation Center.

Reporter Salinger toured the San Bruno jail with Sheriff Dan Gallagher in late January 1953 and wrote a detailed profile of the facility, published on February 6th and 7th across the front page of the Chronicle.

The headline on Salinger’s first article was “S.F. County Jail Is Too Much Like A Penitentiary”. Sheriff Gallagher’s first quote to Salinger as they began their tour was “This is a fine plant. But if we had it all to do over again, I think we would build it a lot differently… a lot differently”.

It is interesting to contrast Gallagher’s comment with the direction local county jail populations were headed over the next twenty years.

The “more serious criminal” population demographic that emerged in the 1960s and 70s would at first pressure jails to have more secure and separate housing areas. Then almost immediately after that era, direct supervision-designed facilities emerged which successfully combined better security with housing area rehabilitation activities.

Writing about the San Bruno jail, Salinger noted there were 525 men in the facility and only 218 of those had work assignments. The prisoners were locked into their tier cells each day at 3:30PM and released into the tiers at 8:15AM the next morning.

On the positive side, in 1952 over 230,000 pounds of vegetables were grown on the County Jail No. 2 farm—enough to feed the jail’s inmates and send surplus to the Kearny Street jails, SF General Hospital, and the Laguna Honda Home.

But most startling to reporter Salinger was the fact that every day between the hours of 4PM and 8AM only one captain and two deputies were on duty in the entire San Bruno complex.

Part 2 of Salinger’s piece was a look into the future of local and State corrections: a profile of a local organization called the Northern California Service League.

Founded in 1948 by State Court of Appeals Justice Raymond Peters, the League brought together a number of charitable organizations to help jail inmates get the kinds of basic things the system couldn’t: everything from contacting their families, to being fitted with false teeth to getting eye glasses.

This was the tip of a new wave of support and rehabilitation in local corrections, and credit Sheriff Dan Murphy who first allowed Service League representatives into San Francisco’s jails to conduct private interviews with prisoners.

From their small office at 353 Kearny Street the Service League also worked with labor unions and employers to have jobs waiting for newly released men.

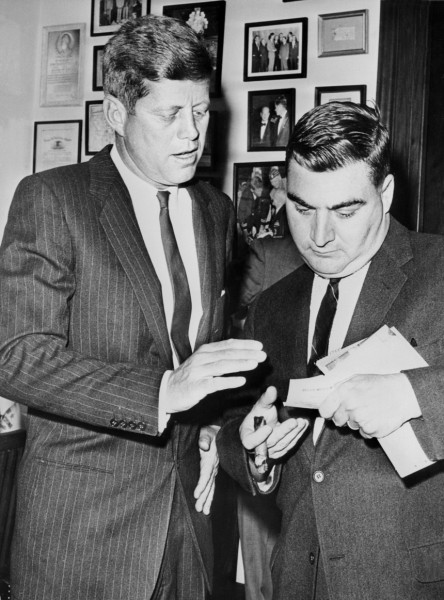

As for Pierre Salinger he soon left the Chronicle to work as an editor for Collier’s Magazine, first on the West Coast then in New York City. In 1957, after Collier’s folded, Salinger was recruited by Senate Labor Rackets Committee chief counsel Robert Kennedy to become the Committee’s first investigator.

In May 1959, Senator John Kennedy of Massachusetts contacted Salinger and told him he was going to run for President in 1960 and he wanted Salinger to be part of his campaign. Salinger became Kennedy’s media coordinator through the presidential campaign of 1960 and then joined President Kennedy in the White House as his press secretary.

Salinger is credited with creating the modern format for presidential press briefings and the press secretary's close but professional realtionsip with the White House media. He died in October 2004 at his home in Le Thor, France at the age of 79.

Another Death at the Top and a Template for Succession

On March 7, 1956 the Civil Service Commission and Board of Supervisors agreed to increase the Sheriff’s salary from $1,125 a month to $1,250 a month-- $15,000 a year.

Sheriff Dan Gallagher, right, inspecting the lunch meal on December 10, 1953 in the County Jail No. 2 kitchen. At left is San Bruno jail Superintendent Bill Hanley and civilian jail chef Stephen Clark. Prisoner food issues were often at the center of the worst prisoners demonstrations and incidents throughout the jail's 72 year history.

San Francisco Mayor George Christopher cited the City Charter when he immediately named SF Coroner Dr. Henry Tunkel to assume the post of Sheriff until he could appoint a successor.

Just over four years prior, Gallagher had been chosen to complete almost all four years of Sheriff Dan Murphy’s final term when he died. Now Gallagher, who had just been elected to his first full term as Sheriff in November, would need a successor to complete his four year term.

Dan Gallagher had run unopposed in the November 1955 election yet still received 172,385 votes, a testament to his popularity and his competence in office.

Almost immediately a legal issue popped up concerning exactly who was eligible to hold Gallagher’s office until Mayor Christopher could pick a permanent Sheriff.

On May 7th, the day after Gallagher died, City Attorney Dion Holman issued a ruling that a 1953 amendment to the State Government Code, which specified that “if the [Sheriff’s] office is vacated it may be filled by a chief deputy”, and that this State law superseded the City Charter.

Mayor George Christopher didn’t argue and immediately appointed Undersheriff John P. Figone to temporarily fill the office.

Christopher also caustically informed the Chronicle that he “had already received requests for the job”. He tersely told the paper that, “The least people might do is to wait until after the funeral to ask for the job.”

On May 10, 1956 Mayor Christopher announced that he was appointing Board of Supervisors’ member Matthew C. Carberry, 44, to serve out Gallagher’s four year term of office. Carberry, a former SF Police officer and assistant to the City Assessor, was a staunch Democrat who had been elected to the Board in November 1953.

Born in Arcadia, Greece in 1907, at the age of 10 George Christopher and his family moved to San Francisco in the South of Market neighborhood known as "Greektown". After getting an accounting degree at Golden Gate College he opened the Christopher Dairy on Fillmore Street. He was elected to the Board of Supervisors in 1945 and lost an election for Mayor in 1951.

He again ran for mayor in the November 1955 General Election and won.

Christopher was a driving force behind the relocation of the New York Giants to San Francisco in 1958 and pushed the building of Candlestick Park. He gained notariety in 1957 when he offered to share his home with Willie Mays and his wife after a San Francisco real estate agent refused to sell a home to Mays in the all white neighborhood of Forest Hills.

In reading between the lines of various newspaper reports at the time, it is easy to speculate that John Figone was one of the people who lobbied Christopher to be the next Sheriff.

Figone had an interesting public service arc in the 1950s. The self-proclaimed “Mayor of North Beach” had a furniture store there and seemed to be constantly positioning himself for public office. After he was appointed to the SF Board of Appeals, almost immediately Figone set his sights on becoming a member of the Board of Supervisors.

John Figone was that politico who worked every dinner, attended every public event, walked in every parade, and shook every hand he could find. In 1953, when Board member Chester MacPhee announced he was up for appointment as the Collector of Customs for San Francisco, Figone lobbied Mayor Elmer Robinson to be appointed to finish MacPhee’s Supervisor term.

On June 15, 1953 Figone was sworn in to take MacPhee’s place on the Board of Supervisors. Amazingly on July 22, 1953, just five weeks after his appointment, Figone unexpectedly resigned from the Board and told the Chronicle he did so “on the advice of his physican.”

And with that, another political career began as Mayor Robinson appointed J. Eugene McAteer, a 38 year old attorney and the owner of Tarantino’s Restaurant on Fisherman’s Wharf, to the Board of Supervisors to replace John Figone. McAteer would later become a two term state senator and an early environmental advocate.

This is a story that simply drips with political intrigue, but little information.

That’s because John Figone made it known that he would like to be the next Sheriff. Then in 1954, only a year after he resigned from the Board of Supervisors, Figone accepted the position of Undersheriff under Sheriff Dan Gallagher. It is interesting to speculate what medical issue would prevent someone from being a city legislator, but allow for a top job in local law enforcement.

Then a year after that, in June of 1955, John Figone told the San Francisco Chronicle that he was seriously considering a run for Mayor of San Francisco. It was a candidacy that immediately went nowhere.

Flash forward to June 11, 1965 when John Figone retired as Undersheriff of San Francisco after an impressive eleven years in the post. A mere nine days later, on June 20, 1965, Figone died at the age of 64.

Matthew Carberry had a four term, sixteen year career as San Francisco’s Sheriff-- one of the longest in the Department’s history. But Carberry’s reign would also be the final chapter of San Francisco’s old school politics-- a perfect example of how dynamic changing times can completely overwhelm the traditional past.

------------------------------------------------------------------

References/sources:

SF Main Library: "NewsBank" San Francisco Chronicle archives; SF Main Library: SF Examiner and SF News Call-Bulletin archives; San Francisco Main Library: "SF Board of Supervisors Journal of Proceedings 1906-1933" collection; “San Francisco Municipal Record”, August 1934; “P.S. A Memoir” by Pierre Salinger; St. Martin’s Press 1995; “The Black Hole of San Francisco” by George Cothran, San Francisco Weekly, August 22-September 2, 1997; Photographer Robert Gumpert; Michael Hennessey; Eileen Hirst; Richard Dyer.