Although Charles Doane’s November 1856 election as San Francisco Sheriff was nullified by the Supreme Court, it was only a matter of months before his name was again placed in contention for the office.

Charles Doane (1812-1862) was originally from Vermont. In 1855, he started the publication of the Evening Bulletin newspaper in San Francisco.

After Sheriff David Scannell was elected to a two year term in September 1855 the City and the County of San Francisco consolidated in 1856. This "new" government meant that existing County office holders had to re-file their "official bonds" as office holders by a certain date. Sheriff Scannell filed his bonds with his surety backers but the Board of Examiners rejected his papers. He then filed a second time and his papers were rejected again.

Then the Board of Supervisors declared Scannell's office vacant, leading to an election in 1856 in which Charles Doane was the only candidate for Sheriff on the ballot. Scannell and the Democrats rejected that portion of the election, claiming that the office wasn't vacant. The California Supreme Court agreed, stating that State law only required the sitting office holder to file his bond, but said nothing about the bond being "accepted" or "rejected". Therefore Scannell had complied with the law and the office of San Francisco Sheriff was never vacated.

Four months after the Supreme Court decision, Doane was selected by the People’s Party Nominating Committee to be its candidate for San Franciso's September 1857 elections. The Committee of Vigilance shut down operations on August 18th and immediately The People’s Party was born. The announcement of Doane’s candidacy took place only ten days after Grand Marshall Doane led the Grand Review parade of the Committee of Vigilance. (Alta, 8-28-57)

Committee of Vigilance Grand Marshall Charles Doane leads the Grand Review Parade at the corner of California and Montgomery Streets-- August 18, 1856.

As "Grand Marshall" of the 1856 Committee of Vigilance, Doane led an army of armed citizen volunteers as they stormed the County Jail, removed two prisoners from the Sheriff’s custody and later executed the prisoners in a display of defiance to law enforcement, the courts, and the City's entire criminal justice system.

Just a few months later, in November 1856, Doane was elected Sheriff and then battled all the way to the California Supreme Court in his effort to assume office.

Unlike in the failed election of 1856, Doane would not be the only candidate for the office of Sheriff in the 1857 election.

The Democratic Party fielded a whole slate of candidates and endorsed John Harrison for Sheriff. Harrison was a deputy sheriff who had served under both Sheriff William Gorham and Sheriff Scannell. Although the Democrats expected to continue its line of elected officials, the 1857 election began the decline and fall of the Democrats and the emerging dominance of The People’s Party for the next ten years.

The office of Sheriff was one of the few lucrative elected positions at the time. The Sheriff had no set salary, but was authorized to charge fees for the services of the office and required to pay for the expenses of the office from those fees. Any revenue beyond the office's expenses became the Sheriff’s income.

In 1857, the Alta newspaper noted that “The Sheriff is paid in fees, amounting, according to a low estimate, to $35,000 a year, of which $20,000 or $25,000 remains a clear profit after paying all the deputies and other necessary expenses. The profits of the office are, however, estimated to be somewhere between $30,000 and $50,000. (Alta, 8-24-57)

This estimate was probably overstated by quite a bit. Sheriff Doane was the first Sheriff to file an annual report, and he reported total receipts for six months in the amount of $5,000. (Municipal Reports, 1860)

In spite of the Committee of Vigilance’s efforts to clean up the body politic in San Francisco, elections were still the object of hard campaigning and underhanded tactics, as illustrated by this comment in the Alta:

“Election Tricks. Already the political wire-pullers are at work getting up their tricks. Last evening, a small slip of paper was brought to our office as a sample. The slip of paper was nicely gummed on the one side, and on the other, in neat capital letters, the words “John Harrison.” This name, of course, in intended to be pasted over the name of Charles Doane, Esq., the People’s candidate for Sheriff.” (Alta, 9-1-57)

Obviously, Charles Doane had the endorsement of the Daily Alta.

Despite the dirty tricks and a hard fought campaign, Doane handily won the election of 1857 with 6,214 votes to Harrison's 4,045 votes.

Within days of the election Doane had filed his official $100,000 bond with over a dozen backers, including Sam Brannan and future Mayor, Adolph Sutro. (Alta, 9-23-57) Sheriff Doane assumed office in the first week of October 1857 and was in the business of posting Sheriff’s sale notices on the front page of the Alta almost immediately. (Alta, 10-26-57)

Along with his duties of enforcing court orders and operating the county jail, the local Sheriff was responsible for enforcing the death penalty as ordered by the local court. In this capacity, Charles Doane became “the hangingest” sheriff in San Francisco history. During his two 2-year terms as sheriff, Doane accompanied five men to the gallows-- two during his first term of office.

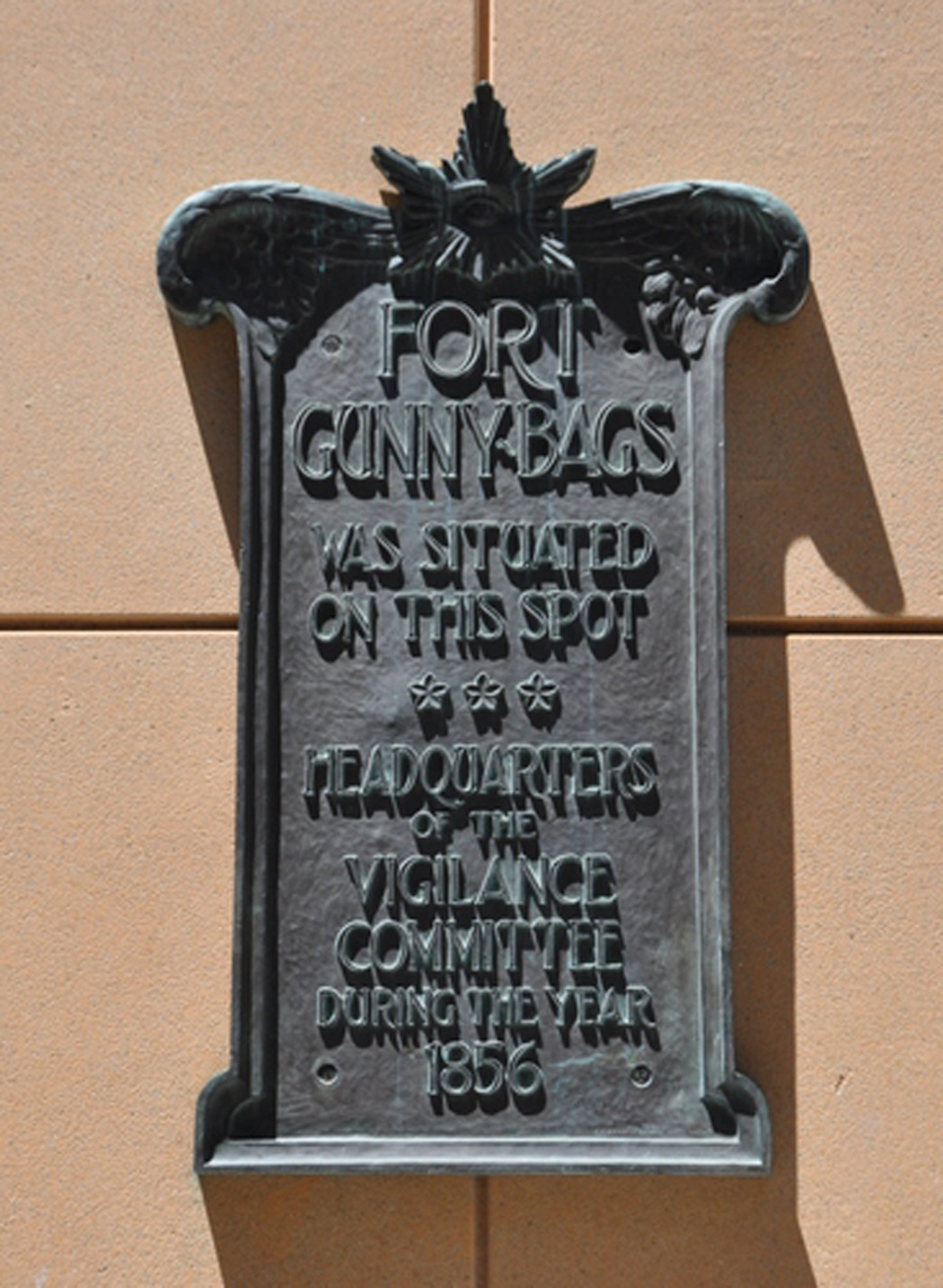

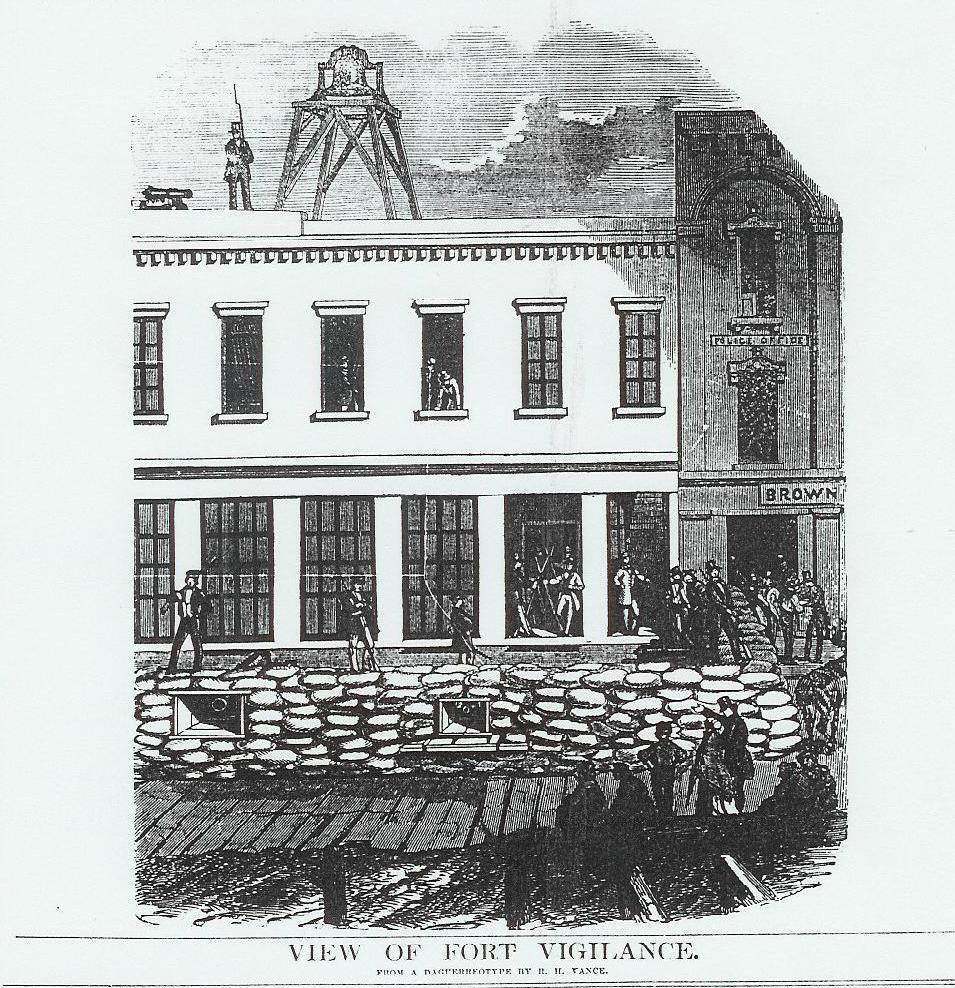

The Committee of Vigilance called their headquarters "Fort Vigilance". The converted warehouse at 243 Sacramento Street (between Front and Davis Streets) was used by the Committee in 1856 for a variety of tasks: Committee meetings, military drills and as an armory-- the repository for the Committee's weapons. The front of the building was the scene of many vigilante hangings.

This photograph was taken by George R. Fardon in June 1856. Charles Cora and James Casey were hanged from the second story window of this building. The bell on the roof is now on display at The Society of California Pioneers at 300 4th Street San Francisco.

The Committee's headquarters was known by most San Franciscans as "Ft. Gunnybags" for the hundreds of sandbags, complete with cannon ports, that ringed the outside parimeter of the structure.

Justice moved a little more swiftly in San Francisco in 1858. Charles Mewse was convicted of murdering the proprietor of a dance cellar named Peter Becker. The murder took place on June 4, 1858.

Mewse was tracked down, arrested and held in the Broadway Street county jail. On October 3, 1858 he was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging at the county jail. Mewes was executed on December 12, 1858-- just six months and 8 days after Peter Becker was killed.

Mewse was a thief with a very bad temper. He had already been in prison in his native Germany for murder before coming to the United States. Mewse settled briefly in Baltimore, but moved to California after brief service in the Army.

The murder was a particularly grisly one. Peter Becker was found in the back yard of his business, his corpse badly mangled, his hands tied behind his back and a cloth gag covering his mouth. After the conviction, Mewse confessed that he had been drunk when he beat and robbed Becker of $100.

While in jail Charles Mewse was apparently a model inmate and had a friendly relationship with the deputy sheriffs assigned to the jail. As profiled in the Daily Alta newspaper, Mewse “in every respect conducted himself with the most perfect propriety. To the keepers of the prison he is indebted for not only administering to him words of comfort, but rendering such substantial aid as his necessities required. In lieu of the homely prison fare, he has oft times been provided with delicacies, for which he has continually expressed his gratitude.” (Alta, 12-10-58)

His execution was well documented in the Daily Alta newspaper:

“Upon entering the prison, at 12 o’clock, we found all arrangements perfected for the execution. In the anteroom was the coffin, ready to receive the remains of the murderer. The scaffold was erected in the rear of the jail-yard, under the superintendence of Mr. H. Dewel, and was very strongly constructed. Its dimensions were 8 x 10 feet; the floor ten feet above the lower platform, and nine feet and a-half below the cross-beam to which the rope was fastened. Underneath the trap was a bolt drawn by a lever on friction rollers. A heavy weight was attached to the drop to prevent it from swinging.

"The hours of one o’clock having arrived, Sheriff Doane repaired to the cell of the culprit, and in a few moments thereafter the rear door of the prison, just opposite the scaffold, opened, and the prisoner, arm in arm between the officers, walked out, and, with a firm step, ascended the ladder. . . . The prisoner stepped forward on to the trap door, and looked earnestly down upon the group clustered about the foot of the scaffold. He was perfectly self possessed, and evinced no symptoms of weakness, although the close observer might have detected an unusual pallor spread over his cheeks as he surveyed the scene before him.

"The culprit was neatly dressed in a white shirt, brown pants, black frock coat, black satin vest and a black cravat. His hair was arrayed with scrupulous care, and his appearance was becoming the solemn occasion.”

Sheriff Doane asked the condemned if he had anything to say and Mewse made brief remarks, thanking his spiritual advisors and telling the observers that it was their duty to warn others not to follow his path. A prayer followed his comments from an attending minister.

From the Alta: “Deputy Sheriff Ellis then read the death warrant, after which ropes were bound about his arms and ankles, noose adjusted around his neck, and the black cap drawn over his eyes. The officers stood apart, the slide pulled, and the unfortunate victim dropped into eternity. After a few convulsive struggles, the body hung motionless for the space of thirty minutes after which the attending physicians having pronounced life extinct, the remains were deposited in the coffin, and given into the keeping of the Sheriff for internment.

“During the execution, which was conducted with great solemnity, the neighboring house-tops were covered with persons; officers, however, were stationed at every point. . . . We have never witnessed a more orderly execution. About one hundred persons were present within the walls of the prison.

“The greatest curiosity was manifested by the prisoners whose cells overlooked the prison yard, and in their windows might have been seen mirrors so adjusted as to command a view of the scaffold. Broadway, in front of the jail, was thronged with persons, who, despite the rain, which fell heavily, stood in the street until the execution was over. On the south slope of Telegraph Hill hundreds of persons, actuated by morbid curiosity, collected to catch a glimpse of the scaffold and the scenes enacted upon it.”

William Morris, known about town as "Tipperary Bill", was described by the Evening Bulletin as “one of the most hardened wretches possible to conceive” and as “one of the most desperate and apparently incorrigible criminals ever seen.” (6-10-59) His final criminal act was one of the murder of Richard Doak who had the misfortune to argue with Bill in a saloon on Pacific Avenue. After the argument Morris waited outside the saloon and then shot Doak in the neck when Doak emerged from the bar. Morris then fled town, but was arrested near Benecia not long thereafter. He was convicted of murder in March of 1859 and walked to the gallows in the county jail yard a scant ninety days later.

The execution of William Morris was performed in a fashion similar to that of Charles Mewse. The same scaffold was set up in the jail yard, but this time Sheriff Doane called upon the Chief of Police and the National Guard to help maintain order on Broadway in front of the county jail and on the hillside behind the jail. By the time of the execution, the “incorrigible” Morris had gained religion and went to the gallows with a small crucifix in his hands. His last words were those of forgiveness of everyone present with a “God Bless you all” added for good measure.

After the trapdoor was sprung and the body allowed to dangle for thirty minutes, Morris was placed in a nearby coffin. According to the reporter from the Evening Bulletin, “While lying in it, the noose and cords were removed and the cap taken off, leaving the face, white like marble. There was no distortion whatever; the eyes were closed, and a smile seemed to play about the lips.”

Again, about one hundred observers were in attendance, including reporters from several newspapers. A sketch of the execution later appeared in The California Police Gazette.

Charles Doane remained a popular figure throughout his first term as Sheriff and was again the People’s Party candidate for Sheriff in the election of September 1859. According to the Alta’s endorsement on election day: “He took the office when records were in a chaotic and wretchedly confused condition, and he has restored it to order. He drove out the crowd of corrupt political leeches who had long fattened upon its emoluments, and put good and true men in their places. Not a single duty has been left unperformed; not a word can be uttered that should lower him in the estimation of the people.” (Alta, 9-7-1859)

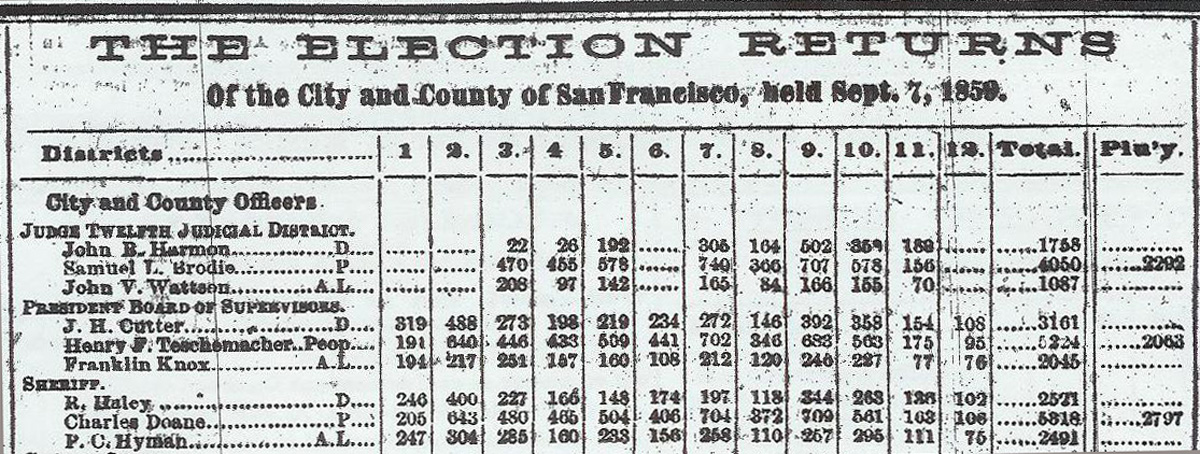

In spite of the ringing endorsement of the Alta, Doane did not run for reelection unopposed. The Democratic candidate was Robert Haley and there was also an American Labor candidate named P.C. Hyman. Concern about chicanery at the ballot box continued to be a matter of concern. The People’s Party offered a fifty dollar reward for the arrest and conviction of anyone voting illegally. Misleading political advertisements were placed in the local press, with two different slate cards attributed to the Regular Democratic Party, one listing P.C. Hyman as their candidate and the other touting Robert Haley. It is possible that this confusion among Democratic voters helped split the vote between Doane’s opponents.

Nevertheless, Doane easily won the election, gathering 5,318 votes with his two opponents receiving about 2500 votes apiece. (Alta, 9-14-59) News interest in this election quickly disappeared when one of the most notorious incidents in San Francisco history occurred six days after the election. The fatal duel between Senator David Broderick and Judge David Terry took place at Lake Merced on September 13, 1859.

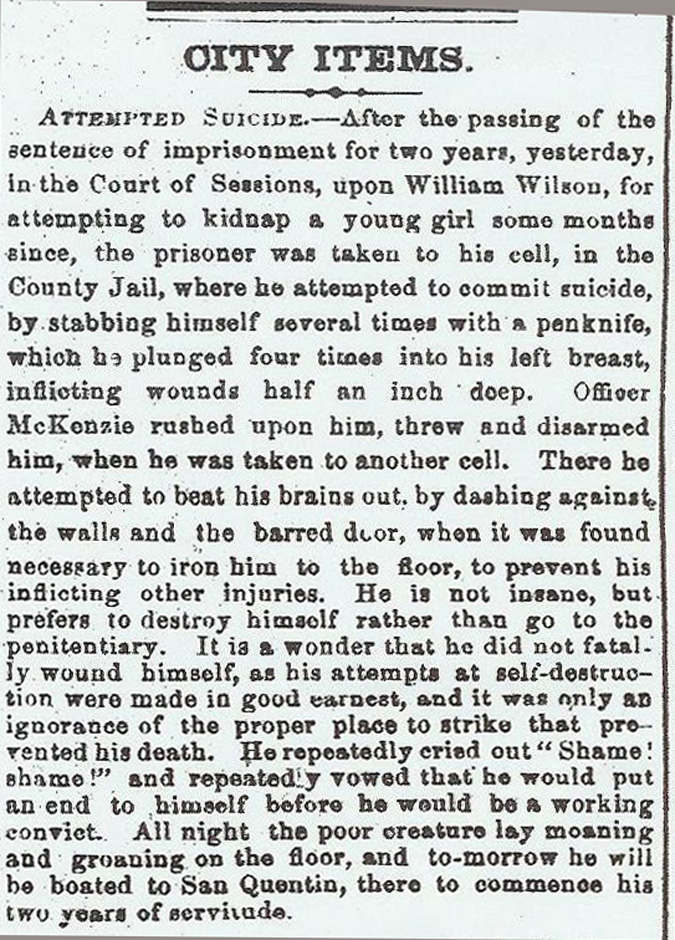

Sheriff Doane’s second term of office had little controversy. There was public interest and newspaper coverage of an attempted suicide in the Broadway jail in September 1860, but sheriff's deputies intervened to stop the prisoner from stabbing himself to death with a penknife.

The Broadway Street jail housed about seventy-five prisoners per day and other than staff costs the primary operating expense was food. The Board of Supervisors put the provision of food for prisoners out to bid, seeking bidders who could guarantee costs no higher than twenty-five cents per day per prisoner. According to the bid, prisoners were expected to receive the following daily diet: one pound of bread (from superfine flour), one pound of potatoes, one gallon of water and one pound of fresh beef. (Alta, 9-23-1861)

Sheriff Doane became involved with enforcing out of season hunting laws by issuing a circular reiterating the state Game Law seasons for the hunting of quail, duck, partridges, elk, deer and other creatures. (Alta, 3-11-61)

At some point during his term as Sheriff, the system of fees going to the Sheriff was abandoned and a salary was set. In February 1860, the salary of the Sheriff was $10,000 per year. This may have represented a considerable loss of income compared to the former fee system, but it was still a healthy salary compared to his Undersherff ($300 per month) or his deputies ($200 per month). (Alta, 2-22-1860)

A year later, the State Legislature passed a law setting salaries for City and County officers and the Sheriff took a $2000 cut in pay. By June of 1861, his pay dropped to $8,000 per year, with the Undersheriff receiving $2400 per year and his deputies earning only $1500 yearly. (Alta, 6-13-1861) Even so, the Sheriff remained the best paid City and County employee. The annual salary of the elected District Attorney was only $4000 which was better than the Mayor who was paid only $3000.

In the midst of the routine of running the jails and performing other daily duties, the role as executioner continued. During his second term, Sheriff Doane carried out three executions in the jail yard.

James Whitford was hanged in the county jail yard in September 1860. He had been convicted of the murder of Edward Sheridan, the owner of a bar who was well known for being slow to pay the help. When Sheridan failed to pay Whitford, Whitford followed him from the bar one evening and shot him in the back. Whitford had been in several prior violent scrapes with the law and suffered from a crippled leg which was the result of being shot by a police officer some years earlier. His distinctive limp helped identify him as the killer.

Sheriff Doane, as was the custom of the day, sent out invitations to the execution and the editor of the Alta was nice enough to print his in the paper. Probably anticipating a bevy of curious citizens wishing to view the execution, the invitation was footnoted: “Please show this ticket at the door of the Jail.”

The execution routine was much the same as the previous two, although this time the coffin was displayed in plain sight, just to the left of the gallows. As Whitford was escorted to the noose, he “gazed half-abstractedly at his coffin as he passed.”

“The heat was intense, as the sun’s rays were reflected against the whitewashed prison walls, and the prisoner seemed to breathe with difficulty, and perspired profusely after he reached the platform. When told he could speak his last words, he began his brief remarks by saying, 'Gentlemen: On a solemn occasion like the present, you will not expect me to make a long oration'. Actually, many would have expected the opposite. He then asked for prayers on his behalf and thanked those who had comforted him in his last days, including 'my sincere thanks to the officers who have been in attendance upon me since my trial'. (Alta, 9-22-60)

“Four stout leathern straps were used to bind him. One of them was passed around his elbows, securing them behind; another went round his hips, holding his wrists to his side; another fastened his knees together, and a fourth his ankles. After this, he cried out in an audible voice, ‘Jesus, have mercy on me!’ and then followed the prayers conducted by the priests, who frequently pressed the cross to the lips of the doomed man that he might kiss it.

"In drawing the noose the Deputy-Sheriff made two or three ineffectual attempts to fit the knot properly under the ear – distracting the attention of the condemned from his prayers. Finally, all was arranged, the black cap was drawn, the trap sprung, and the prisoner fell a distance of eight feet, the manila rope stretching with the heavy weight upon it. There was a slight convulsive movement, a general raising of the body, a lifting of the shoulders and all was over. The body was cut down after hanging about half an hour.” (Alta, 9-22-60)

Albert Lee murdered his estranged wife. Lee was an African American, described as a “mulatto” in the local press, with some social standing in the community. He had been the personal aide or valet of Colonel John C. Fremont, one of the great western explorers and the Republican candidate for President in 1856. After Lee’s marriage fell apart, he made many attempts to reconcile with his estranged wife and her family, but with no success. On July 9, 1859, he waited outside his wife’s family home until she emerged. Then he walked up to her, shot her in the head and then shot himself in the chest.

Lee fought his case vigorously and attempted to mount an insanity defense, primarily on his suicide attempt. After his conviction, he appealed the case to the California Supreme Court, which heard his appeal, but upheld the conviction. He and his supporters then applied to the Governor for a commutation of sentence, but got no response.

By now, the procedure for executions was rather routine. On execution day, March 3, 1861, police were called out to keep the crowds from disrupting commerce on Broadway and from gathering on rooftops, with mixed results.

The Evening Bulletin set the scene: “Quite a crowd of those who are irresistibly attracted to any spot where some horrible thing is to be enacted, gathered into Broadway, in front of the jail; and on the surrounding heights, especially on the top of Telegraph Hill, there were knots of men and a few women looking out, hungry for some glimpse of the spectacle. It was little they could see, however, and policemen were placed on the roofs immediately overlooking the yard, who prevented any morbidly curious people, except the occupants themselves of the housed, from feasting their eyes on the violent death of a fellow being.

“Lee wore a brown frock coat, tightly buttoned, and a grey hat. He looked so happy that it was difficult to believe he could be the man whose end was so nigh. Though mulatto, with his hat on, he would readily pass for a white man.” (Evening Bulletin, 3-1-61)

Lee made brief remarks, including that he was “here today to be executed for the crime of shedding human blood – the blood of that one whom I loved above all on earth. I am willing to shed my blood as a sacrifice for her life. I am happy to go.” After “an impressive prayer from Mr. McAllister,” Lee was hanged. As the Alta noted, “The ceremony was conducted with that due solemnity which has heretofore characterized the official duties of our Sheriff.” (Alta, 3-2-61)

It should be noted that unlike most of the other executed felons in San Francisco, Lee did not have a prior life of crime. Nevertheless, as historian Kevin Mullen documents in "Dangerous Strangers" (p. 109), San Franciscans were particularly harsh regarding the murder of women, possibly because there were so few of them in town at the time. One third of those executed in San Francisco between 1850 and 1900 were the murderers of women. Although Albert Lee’s case fits a classic definition of domestic violence, his was not the first execution arising out of a domestic dispute. William Sheppard was executed in July 1854 for the murder of Henry Day, the father of Sherppard’s girlfriend, presumably because Mr. Day refused to allow Sheppard to marry his daughter.

Barely 90 days after Albert Lee’s execution, Sheriff Doane escorted one last murderer to the gallows. John Clarkson, “a Negro,” had murdered Caroline Park, “a mulatto,” on December 1, 1860. Clarkson was about 26 years of age; Caroline Park was seventeen. Unlike the more popular Lee, Clarkson generated very little sympathy or legal support and went to his death only seven months after the crime.

By the day of Clarkson's hanging, June 4, 1861, Sheriff Doane had a fairly routine procedure in place for executions. But even a routine can be turned upside down, as Clarkson's hanging would demonstrate. It is rare when a condemned man mounts the gallows and then entertains the assembled with a song.

“The doomed man met his death with seeming indifference almost unparalleled. He mounted the scaffold unaided, followed by Sheriff Doane, his five Deputies, Rev. A.B. Smith (colored) Pastor of the Zion Methodist Church.” After a brief statement, Clarkson, “joined his Reverend assistant in singing the hymn, selected by himself, commencing with – My God, the spring of all my joy, The life of my delight.”

Between 1850 and 1900 only three African Americans were executed in San Francisco; all three for what would now be considered domestic violence.

Sheriff Doane made administrative history when he became the first Sheriff to file an annual report, which was published as part of The San Francisco Municipal Reports. His report, which covers only the last six months of his time in office is a bookkeeper-like summary of Department activities, even though he prefaces his report with the caution that, “From the peculiar nature of the business of the Sheriff’s Office, it is impossible for me to offer you a report as ample as I desire to.”

Doane reports the income and expenditures of the office and discusses the various duties, including having transported 31 prisoners to the Penitentiary and 40 to the State Insane Asylum.

Even in the early days of the office, the office of Sheriff was a litigious position. Doane reports, “The Sheriff is sued almost daily,” usually for challenges to court orders that he has carried out."

He also reported on the jail population, having received 282 prisoners during the six months, with 46 remaining at the time the report was filed. The state of the Broadway Street jail was not good. “The floors of the cells are literally rotten, the roof is beyond redemption and must be entirely renewed. . . . Bunks should also be supplied for every cell which is not now provided with them.”

The sword presented to former Sheriff Charles Doane. With gold head embedded in quartz, the California coat of arms on the scabbard, and a gold shield. Photo taken in the City Hall office of Sheriff Michael Hennessey, 2010.

Friends and supporters of Sheriff Doane honored his retirement by presenting him with an engraved “regulation sword, with gold head embedded in quartz, California coat of arms on the scabbard, and a gold shield” inscribed by his admirers. The sword remains in the possession of Sheriff Doane’s ancestors.

As he accepted the sword, the still feisty Sheriff said, “I need not say that I shall in future years not regard the beautiful and keen blade entrusted to me as a mere mark of esteem only; for you, gentlemen, each and all of you, know that should an opportunity occur, it will prove its temper with a determined hand to wield it, in defence of the integrity of the Constitution and the flag of our glorious Union.” (Alta, 10-23-1861)

Sheriff Charles Doane died only a year later.

The Alta mourned his death immediately and commented, “it is a historic truth, that during the tenure of his office in connection with the proceedings of the Vigilance Committee, it was owing solely to his efforts that not one drop of innocent blood was shed at a time when the passions of men ran counter to their instincts; when all was chaos . . .. Without Charles Doane, anarchy would have run riot on the novelty of success. . . What great patriots have been to nations, he was to San Francisco – its liberator, and the guardian of its honor.”